Catch Me If You Can: What are Trojan Asteroids?

Their origins, dynamics, and what the Lucy mission reveals about the evolution of our Solar System.

This week I’m happy to introduce a guest post by Samreet Dhillon. Samreet is a physics post-graduate and part-time science communicator, whose primary interests lie in Quantum Field Theory and Astrophysics. You can find his newsletter, ‘Bohring’ , on Substack.

Last month, I finished reading Astronomy in Minutes, a brilliant guidebook by Giles Sparrow. Page 78 and the accompanying picture caught my attention the most. The topic was Trojan Asteroids. Despite being a physics post-grad, I didn’t know about them!

I had always pictured asteroids as rocks drifting aimlessly in the belt between Mars and Jupiter, or perhaps as those near-Earth objects that occasionally make headlines. Trojan asteroids don’t fit that image at all. They are remarkably “disciplined” objects that share a planet’s orbit without ever colliding with it. Instead of being swept up by a planet’s massive gravity, they maintain stable, independent orbits around the Sun.

For billions of years, they have occupied the same celestial neighborhoods with remarkable stability. This orbital harmony poses a very natural question: How does a relatively tiny body resist the overwhelming gravitational pull of a nearby planet to maintain its own path?

Then I remembered the classical mechanics lectures from my good old undergraduate days. I revisited my notes and ended up binge-reading online. Not only that, I created my own Python simulation!

What Are Trojan Asteroids?

Formally,

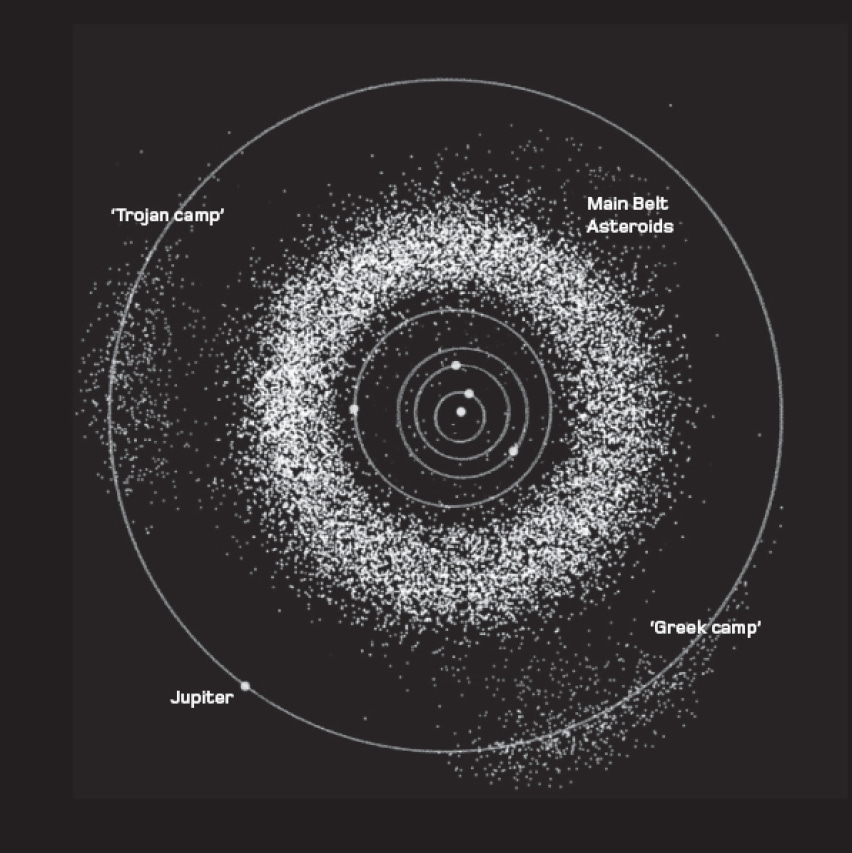

Trojan asteroids are minor celestial bodies that share a planet’s orbit, clustering around two specific regions known as the L4 and L5 Lagrange points. These gravitational sweet spots are located 60° ahead of and 60° behind a planet along its orbital path.

The most famous Trojans belong to Jupiter, who hosts several thousand of them. They are divided into two camps:

The Greek Camp: Occupying the leading L4 point.

The Trojan Camp: Occupying the trailing L5 point.

This naming convention comes from Homer’s Iliad, and it stuck. The individual asteroids are themselves named after the heroes in the story of the Trojan War.

While Jupiter dominates the conversation, Trojans have also been identified orbiting Mars, Uranus, Neptune, and even Earth. Saturn is a special case; we will return to it later.

The Physics of Lagrange Points

To understand their strategic location, we must examine the Restricted Three-Body Problem through two different lenses. In this scenario, we have a massive primary (the Sun), a secondary mass (a planet), and a third body of negligible mass (the asteroid).

A Bird’s-Eye View of the Inertial Frame

Imagine hovering far above the Solar System against a frozen backdrop of stars. In this frame, the physics is straightforward:

Jupiter and its two Trojan swarms revolve around the Sun in massive, nearly circular orbits.

The L4 and L5 regions act as “dynamic parking spots” that rotate in lockstep with Jupiter, perpetually maintaining their 60° offset.

From this perspective, an asteroid performs a triple-action: it orbits the Sun, wobbles within its Lagrange region, and experiences slight fluctuations in its orbital radius.

A Stationary View of the Rotating Frame

The asteroid’s true relative motion emerges when we switch to a Rotating Reference Frame. So imagine standing on a carousel spinning at the exact rate of Jupiter’s orbit. In this frame, the 12-year orbital transit of Jupiter and asteroids is cancelled out.

Jupiter appears stationary.

Tadpole Orbits: Most Trojans trace small, kidney-bean-shaped paths around L4 or L5.

Horseshoe Orbits: If an asteroid possesses enough energy, it may embark on a much longer journey, traveling the long way around the Sun to visit the opposite Lagrange point before swinging back.

Why are L4 and L5 Special?

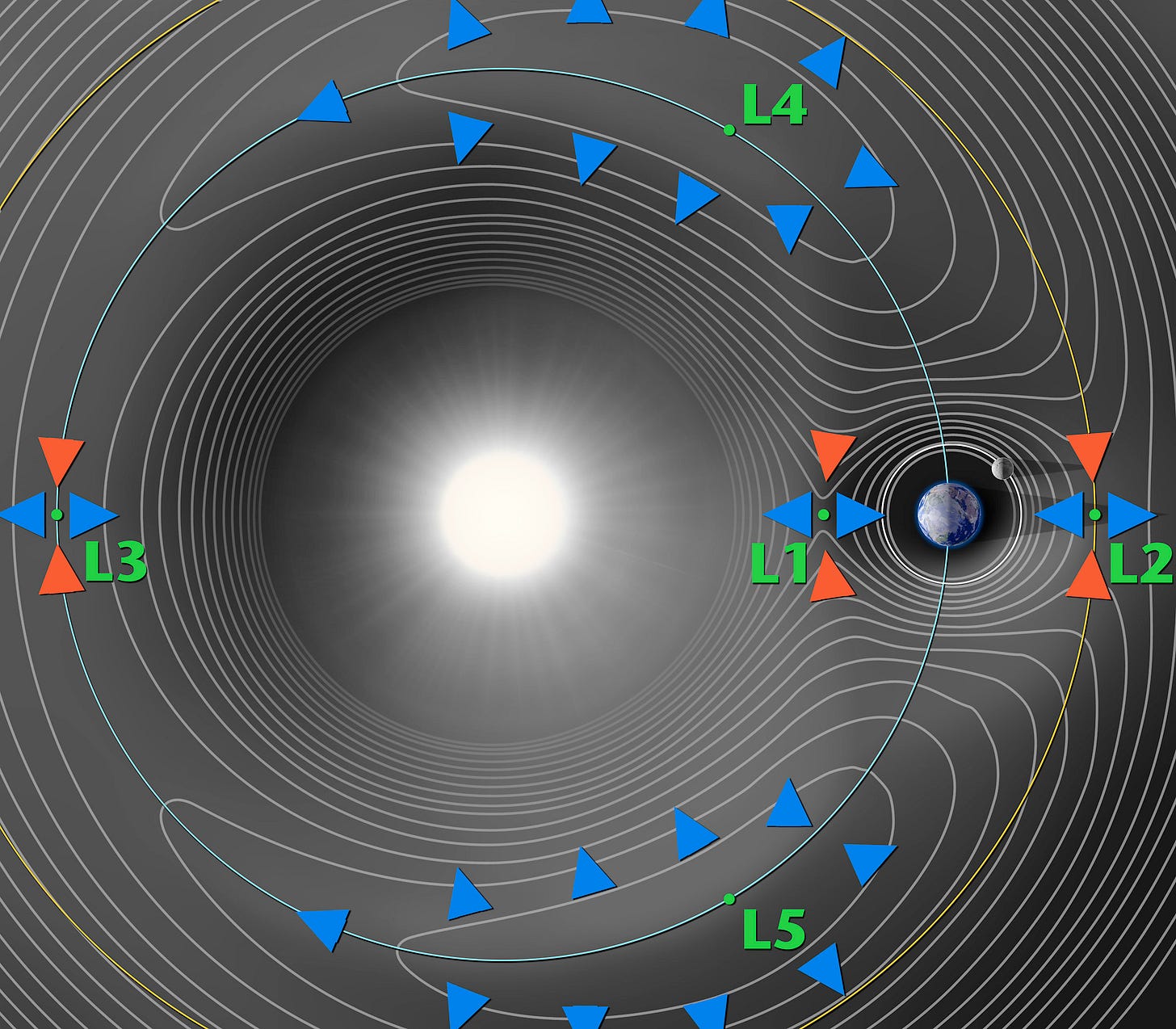

In the figure above, you can see five equilibrium points. In the Restricted Three-Body Problem, these Lagrange points are where the gravitational pull of the Sun and the planet perfectly balance the centrifugal force of the asteroid’s motion.

Not all these points are created equal:

L1, L2, and L3: Discovered by Leonhard Euler, these are unstable. Occupying them is like trying to balance a marble on the tip of a needle; the slightest perturbation sends the object drifting away.

L4 and L5: Discovered by Joseph-Louis Lagrange, these can be stable. They act like wide, shallow bowls. If an asteroid wanders away from the center, the Coriolis force (an apparent force in our rotating frame) deflects it back into a loop, keeping it trapped in a stable Tadpole orbit.

The Routh Stability Criterion

Stability at L4 and L5 is not a universal guarantee; it depends entirely on the mass ratio between the two large bodies. According to the Routh stability criterion, the Trojan points are only stable if the secondary body (the planet) is significantly smaller than the primary (the Sun). Specifically:

(Or, the planet must be less than approximately 4% of the Sun’s mass).

Jupiter, Earth, and the other planets easily satisfy this condition, allowing them to shepherd long-lived Trojan populations. Only two Earth trojans have so far been discovered: (706765) 2010 TK7 and (614689) 2020 XL5.

Our Moon’s relatively low mass and the overwhelming, chaotic gravitational influence of the Sun and Earth make it a case where the Routh criterion is not satisfied.

The Saturn Mystery

Interestingly, while Saturn satisfies the Routh criterion, it lacks a significant Trojan population around the Sun. This is due to gravitational interference from Jupiter. The “Great Purge” caused by the nearby gas giant’s massive pull destabilizes Saturn’s Sun-centered Trojans over long timescales. However, Saturn demonstrates the same physics on a smaller scale: it has Trojan moons (like Telesto and Calypso) that sit at the L4 and L5 points of the Saturn-Tethys system.

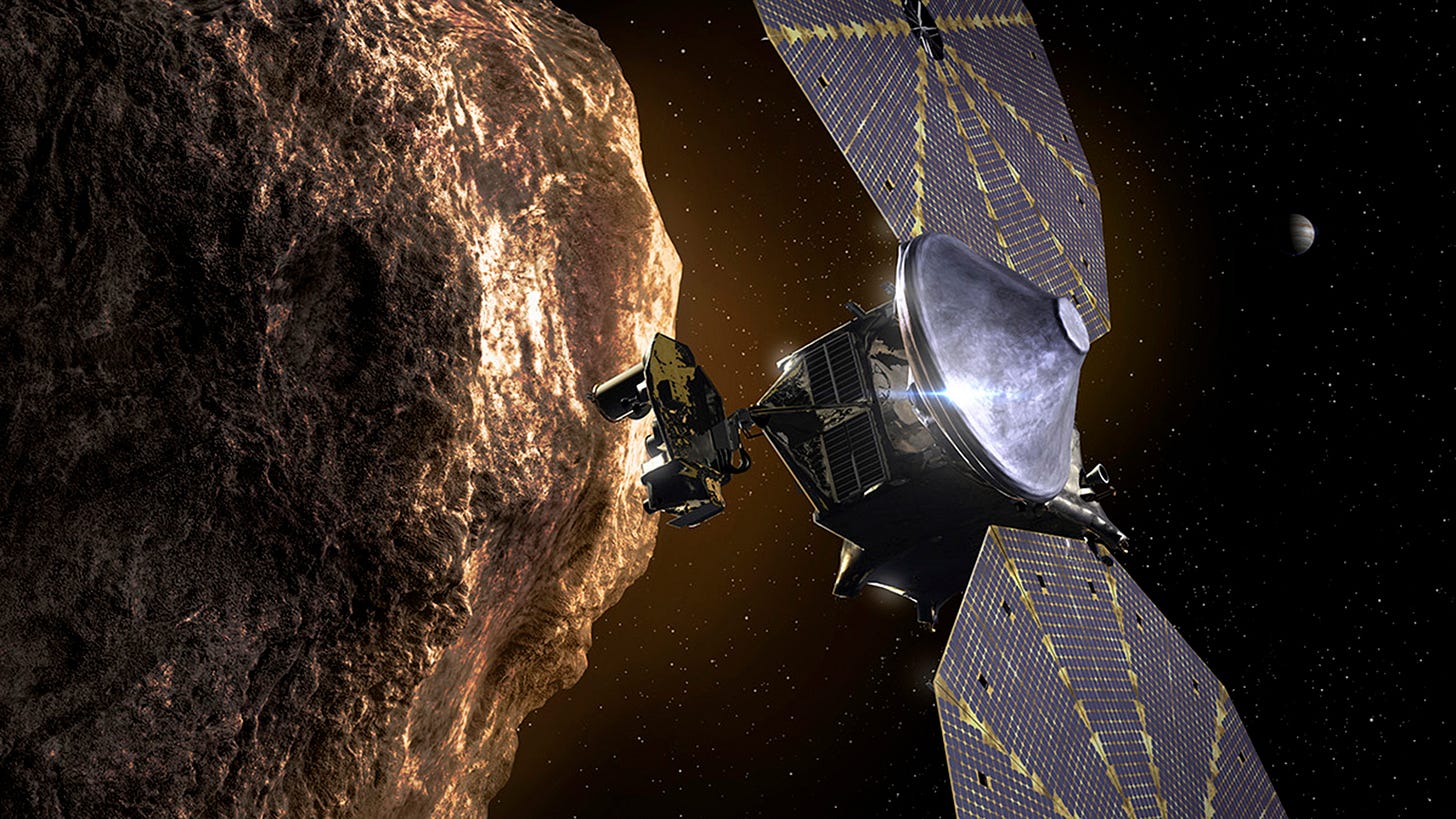

The Lucy Mission: Visiting Fossils of Planetary Migration

Launched by NASA in October 2021, Lucy is a high-stakes reconnaissance mission to Jupiter’s Trojan population. Over its 12-year journey, it has already visited two main-belt asteroids (Dinkinesh-Selam and Donaldjohanson) and is now headed for eight Jupiter Trojans (Eurybates-Queta, Polymele-Shaun, Leucus, Orus, Patroclus, and Menoetius) across both the L4 and L5 swarms.

Why the Trojans?

Unlike main-belt asteroids, Trojans have remained dynamically isolated for billions of years. Because many have avoided significant heating or collisional evolution, they serve as the most primitive surviving bodies in the Solar System.

The primary scientific motivation rests on the Nice Model of planetary migration. If the early Solar System was as chaotic as this model suggests, Jupiter’s Trojans should contain material from the inner disk, the outer disk, and even the Kuiper Belt. By comparing objects in both the L4 and L5 swarms, Lucy will test whether these asteroids are a heterogeneous mixture of the early Solar System or a uniform population that formed in situ.

What Lucy is Measuring

While Lucy is not a sample-return mission, its strength lies in comparative planetary science. Its instrument suite is designed to dissect these fossils from a distance:

Spectroscopy (Visible & Infrared): To map minerals, organics, and ices.

High-Resolution Imaging: To study surface geology and cratering histories (which act as a clock for the asteroid’s age).

Thermal Radiometry: To determine the physical properties of the surface regolith.

Radio Science: To calculate the mass and density of these bodies via gravitational perturbations on the spacecraft’s path.

If the Trojans turn out to be compositionally diverse, it would provide smoking gun evidence for large-scale planetary migration. If they are unexpectedly uniform, it will force a fundamental revision of our models of how the giant planets found their current homes. Either way, the results will rewrite the history of our celestial neighborhood.

The Bigger Picture

There is something quietly profound about the Trojan asteroids. They are not dominant or destructive. They reveal how structure emerges from gravity and how stability can thrive within nonlinear systems. They show that the Solar System is far more than a collection of isolated orbits. It is a deeply interconnected, dynamical whole.

These asteroids sit at the precise intersection of celestial mechanics, planetary science, and chaos theory. They are elegant solutions to a gravitational puzzle, written across astronomical time. If you want to understand how the Solar System remembers its past while remaining dynamically alive, Trojan asteroids are a very good place to start.

Very cool! I’m a retired STScI graphic artist and found this very interesting — and am subscribing to your Substack ✨