Has The James Webb Found Life on K2-18b?

Speculation is mounting of a dramatic discovery of life beyond Earth. Here are the facts.

Reader note: By long standing policy I follow the rules of British English on The Quantum Cat, under which “sulphide” is spelt with a “ph”. In American English the same word is written “sulfide”.

Have we already found alien life? According to a recent article in The Spectator, a British magazine, the answer may be a tentative yes. They drew this startling conclusion from the words of several respected commentators, including one astronaut, who each hinted at unpublished work outlining the discovery of life beyond Earth.

Naturally this has resulted in a good deal of speculation. In its most credible form, the story argues that the James Webb telescope has spotted the chemical signatures of life on some faraway world. Since the evidence is still weak, and the conclusions earth-shattering, researchers are sitting on the paper, keeping things quiet until they are more certain they are right.

Nevertheless, the theory runs, the news has started to spread among astronomers. Rumours are being picked up in the press, amplified on Twitter and - in a desperate attempt to keep things under control - denied by those in the know. In its wilder forms, this is all part of a grand conspiracy to normalise alien life, and before long governments will admit that ET has been with us all along.

That last bit, to put it politely, is utter nonsense. But the idea that the James Webb might have spotted signs of life beyond Earth is not impossible. Indeed, the closing quarter of 2023 did see some papers arguing that the telescope has already found these signs, and that a definite discovery of alien life is not far off.

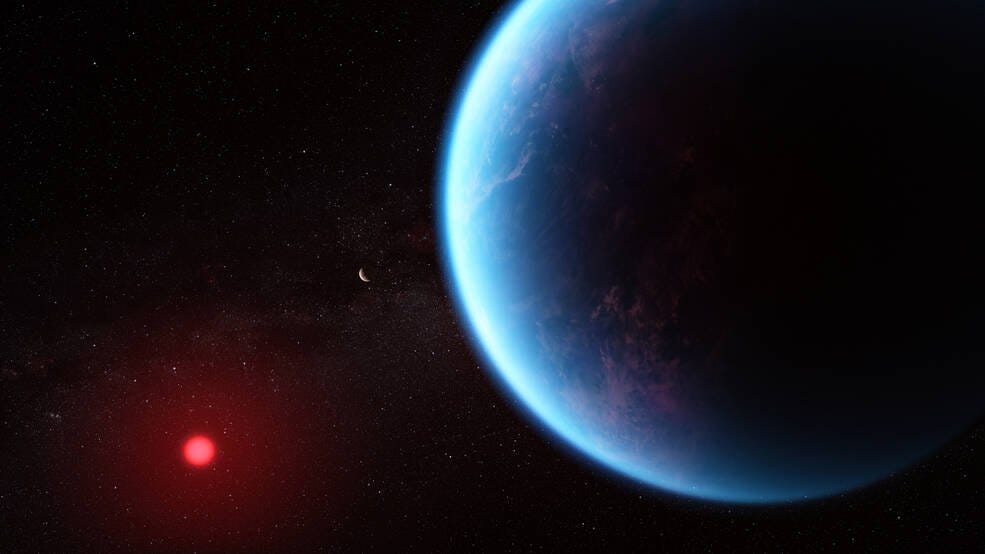

It is likely that the commentators, including the astronaut, were referring to those reports. They centre on a world known as K2-18b, a planet orbiting a faint red star some one hundred and twenty light years from Earth. Data from Hubble and the James Webb show a giant planet, roughly eight times the size of Earth, but one that seems to have an atmosphere rich in hydrogen and a surface covered in deep oceans.

More intriguing, data published last year claimed the James Webb had found evidence of dimethyl sulphide in K2-18b’s atmosphere. On Earth this chemical is a certain sign of life, and so to find it floating through the air of a distant planet is interesting, to say the least. Add that to earlier speculation that K2-18b is a hycean world, a hypothetical type of planet that could be habitable, and you have all the ingredients for a groundbreaking claim of alien life.

Still, caution is to be advised. No hycean world has ever been definitively found, and some argue that they do not really exist at all. Even if they do, it is not certain K2-18b is one. And the signature of dimethyl sulphide was weak: so weak, in fact, that it might not be there at all. Three questions, then, surround this world. Is it really a hycean world? Is dimethyl sulphide really present in its atmosphere? And if it is, does that definitely imply the presence of life?

I. The Hycean Worlds

The idea of hycean worlds first emerged in 2021. Their name comes from their two key characteristics: thick atmospheres made mostly of hydrogen, and deep oceans of liquid water. In temperature they would be similar to Earth, but in terms of mass they are far larger, weighing at least four times heavier than our own planet.

Nothing like this exists in our solar system. Of the rocky planets, only Earth has oceans, and only it and Venus have a thick atmosphere. Neither is large enough to hold on to much hydrogen, which instead tends to escape into space. The larger planets - Neptune and Uranus - do have plenty of hydrogen, but are far too cold to hold oceans of liquid water.

Still, if you take a planet like Neptune, make it a bit smaller, and stick it roughly where the Earth is, you could end up with something like a hycean world. There are planets - K2-18b among them - that fit this description, so it seems reasonable that they might also be hycean worlds.

Back in 2019, Hubble took a closer look at K2-18b. It reported signs of water in a thick hydrogen atmosphere, along with some evidence of icy clouds. Calculations showed that K2-18b should get roughly the same amount of solar heating as Earth does, and so it could feature Earthlike temperatures. This was all very promising, and suggested it could indeed be a hycean world.

Things got even more interesting last year, when researchers pointed the James Webb telescope at K2-18b. Like Hubble, the telescope saw signs of a thick hydrogen atmosphere, filled with gases like methane and carbon dioxide. Notably, however, no signs of water were picked up, and other expected chemicals, including ammonia, were also missing.

Why did Hubble find water when the James Webb didn’t? Some argue that Hubble was mistaken, and the data it returned actually indicated methane, not water. That is certainly possible: the James Webb is much more sensitive, and better at distinguishing molecules. In any case, the failure of Webb to find water is enough to cast doubt about whether any exists there at all.

But there is another clue. The absence of ammonia and the presence of carbon dioxide might point to oceans on the surface of K2-18b. Both are expected side-effects of such an ocean, and some models, therefore, suggest that K2-18b has both a hydrogen rich atmosphere and an ocean, making it a hycean world. However, other studies have found that oceans of lava can create the same chemical signature - and, therefore, that K2-18b has a surface of molten rock.

So K2-18b might be a hycean world. But it could also be a lava world, and perhaps there are no hycean worlds out there at all. At the moment we lack the evidence to say either way for sure. Until we get more data, we cannot be certain what this world really looks like.

II. A Trace of Dimethyl Sulphide?

What about dimethyl sulphide? On Earth this is a chemical often associated with the smell of cooked cabbage or fish. Plankton floating in our oceans produce a lot of it; so much, indeed, that there is some speculation it plays an important role in the world’s climate systems. Regardless, this is a chemical that is very much linked with life, and with marine life in particular.

Why should we care about this? When the idea of hycean worlds was first floated, they caught attention for the idea that they might be habitable. This is controversial. Hydrogen is a powerful greenhouse gas, and so hycean worlds might be very hot. They are also big, so that they are under a lot of pressure. Neither of those things are particularly good for life.

Still, some calculations suggest that a hycean world in the right place could have oceans cool enough for life to evolve. If it does, one byproduct could be dimethyl sulphide, a gas that would appear in the atmosphere and theoretically be detectable by telescopes. If we want to look for life beyond Earth, dimethyl sulphide is a promising place to start.

The scientist behind this idea is Nikku Madhusudhan, a professor of astrophysics at Cambridge University. He is also the lead researcher behind the efforts to examine K2-18b with the James Webb - so it may come as no surprise that he is now claiming to have found dimethyl sulphide there too.

When the James Webb examines the atmosphere of an exoplanet, it produces a spectra much like the one below. It shows how the presence of various molecules in the planet’s atmosphere has affected the light coming from it. Each molecule has its own signature, and thus by careful analysis of these spectra, scientists can work out what molecules are present in a distant atmosphere.

In the case of K2-18b, as shown above, the signatures of methane and carbon dioxide are fairly clear. We can thus be confident that these chemicals are really present. However, the signature of dimethyl sulphide is much less clear. It might be there, but the signal is not really strong enough to say for sure. Madhusudhan may, in other words, be making an awful lot of fuss about a bit of noise.

To clear the question up we need more data. That could come from the James Webb, which might be capable of better resolving the signal with more time. But it may need to wait for the next generation of telescopes, some of which will be designed to sniff out such chemicals with much greater precision. Either way, it is still too early to settle the question of dimethyl sulphide.

III. Life Beyond Earth

Even if K2-18b is a hycean world, and even if dimethyl sulphide is present in its atmosphere, is this enough to claim proof of life? That is a hard question to answer, and what answers exist are often controversial.

What we can say is this: on Earth dimethyl sulphide mostly comes from biology. If we find it on an exoplanet there is a chance it is coming from alien biology. But there is also a possibility that some strange chemical or geological process is creating it, or even something else bizarre that we haven’t considered.

It would, in other words, be a strong and tantalising hint of alien life. But it would - absent other compelling details - fall short of a certain discovery. Even if a new paper is currently being written, outlining more proof of dimethyl sulphide, or some other interesting molecule elsewhere, it is unlikely to meet the standards of evidence that such a dramatic claim would need.

What all this boils down to is simple. The discovery of life beyond Earth would be the discovery of the century. It is, quite possibly, the biggest claim that any scientist can dare to make; a breakthrough that would change the way we see ourselves and the cosmos, that would raise the serious possibility of encountering alien intelligence and that would send echoes reverberating through society.

Claims of having done so thus face a high standard of proof. As Carl Sagan once said, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Alien life is certainly an extraordinary claim. Yet the discovery of dimethyl sulphide, or some other similar chemical, does not meet a high enough bar to count as extraordinary evidence. As long as other possibilities exist - geology, chemistry or whatever else - the threshold to claim discovery of alien life will not be met.

At the same time, we are drawing closer to a point where this changes. Telescopes like the James Webb will keep on finding molecules that might have biological origins. In most cases the data will be weak and the lines only faintly visible. Definitive proof will, in all likelihood, be hard to come by. The conclusions will be controversial. But they will keep coming.

Have we already found alien life? Probably not. But don’t rule the idea out, either. It might not be this year, nor the next, but the chances are good that the evidence will build to a breaking point within the next few decades. Just don’t expect that news to break in The Spectator.

Thanks

What is the special role of the hydrogen atmosphere? Isn't water in contact with hot rocks at the bottom of an ocean enough even if the "atmosphere" is ice as in Titan or Enceldes?

Thanks for this detailed break down!

"I want to believe"... and hopefully someday the sober analysis will justify doing just that.