The False Colours of Astronomy

The stars don't look like the telescopes say they do

Are the colours of astronomical images real? That is, if we were to hop on a spacecraft and fly out to see these objects - these vivid nebulae and these majestic galaxies - would we really see them as our telescopes claim to?

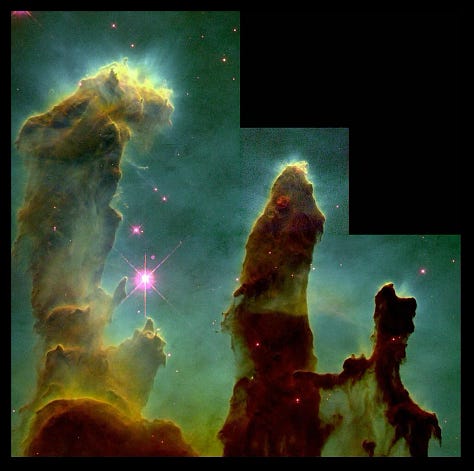

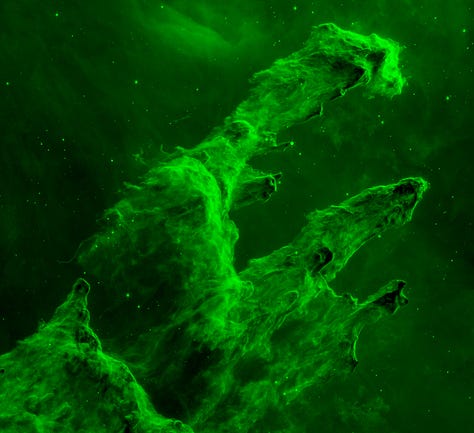

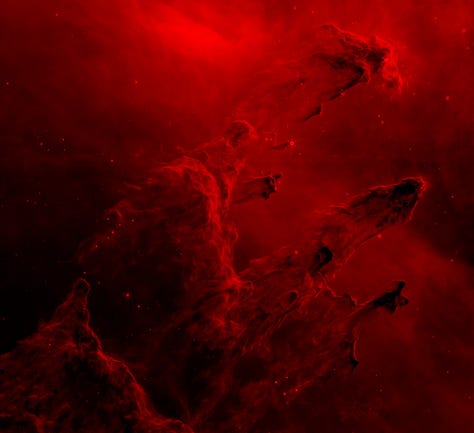

Take, for example, the Eagle Nebula, a cloud of gas and dust in the Serpens constellation. You have probably seen images of it before - the nebula, with its dramatic smoky towers, is a favourite target of powerful telescopes. Within it, and amidst a vast cocoon of gas and dust, new stars are forming; an event that gives rise to its popular name “The Pillars of Creation”.

What do these pillars actually look like, though? If you study the image Hubble made in 1995, they seem brown and opaque, towering like some distant fingers stretching high into the sky. But if you look at another picture, taken by a telescope at the La Silla observatory in Chile, the pillars are a soft pink, standing gently amidst the glittering stars.

Perhaps we can turn to the James Webb, the most advanced telescope ever built, to settle the question? But it too shows something different! To Webb the pillars appear like the orange claw of some ghostly hand, reaching out as it grasps at a sky of shining lights.

What, then, is going on? How can three different telescopes show us three dramatically different images of the same thing? And why do all show it shining in different colours? Has the Nebula changed within a few short years? Or are the telescopes lying, deceiving us to conceal some dark secret?

The easy answer is to say they’re all wrong. In reality the nebula is extremely faint, little more than a tenuous cloud of gas stretching across vast distances. Human eyes - even if they were much closer than we are - could never actually sense enough photons to give it colour. It would thus appear, at best, as a wisp of darkness against a background of cold white stars.

But this is a boring answer, and ignores the fact that there really are colours here, even if human eyes can’t see them. The harder answer, then, is to say these images were taken by different telescopes, each specialised in its own kind of light, and that their purpose was scientific study, and not simply to create beautiful pictures of cosmic wonders.

The View From La Silla

From the deserts of northern Chile, a place sheltered by high and dry mountains and so unaffected by clouds or the lights of human civilization, one can see around five thousand stars with the naked eye. Telescopes can see a good many more - several tens of millions at least - scattered across the entire firmament.

That number reflects the vast size of the universe around us, which stretches for an unimaginable distance in every possible direction. Telescopes have surveyed much of it, and, through the art of astrometry, mapped out its contours. But still, things change - stars sometimes explode, or flare up, or silently vanish; bursts of energy come from black holes or neutron stars; gamma rays, a sign of distant catastrophe, flicker in the far reaches of space and time.

Changes like this can come from any direction, at any time, marked only by the arrival of a sudden stream of photons. Some of our telescopes are thus employed to survey the sky, night after night, in search of such shifts. But as well as coming from any direction in space, photons span a vast range of frequencies.

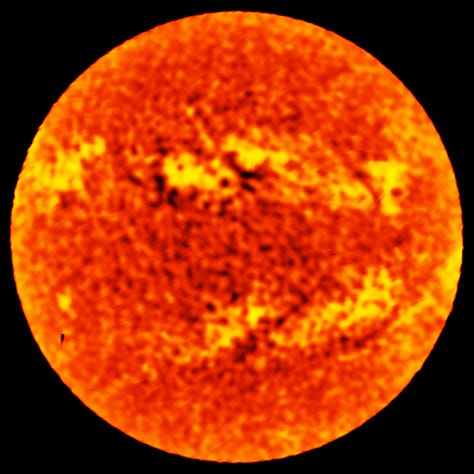

What we can see - what our eyes can sense - is a slight fraction of this vast range. The lowest frequencies, and thus the least energetic, are the radio waves, detected only in 1886 and imagined for the first time just two decades earlier. The highest energy - the gamma rays - were first seen a few years later, in 1900, as science began to probe the strangeness of radioactivity.

Just as the night sky is too vast and incomprehensible to take in at a single glance, so too is this enormous range of frequencies and energies. Partly to reduce this to something sensible, and partly out of technological necessity, telescopes must filter the photons they survey. Observatories limit themselves to frequency ranges, and then narrow even that down by use of filters, to focus only on a single colour of electromagnetic radiation.

Seen in this way, the cosmos can look very different. In radio frequencies the sky is dominated by black holes and flashing pulsars, with the great jets of Centaurus A - driven by an active black hole - spanning an area far greater than the disc of the full moon. Seen in gamma rays, the sky is constantly changing, lit by the flashes of events of terrible power, of supernova and stellar collisions, of magnetic eruptions and other things, of still unknown origin.

In the deserts of northern Chile, at a place called La Silla, astronomers have built some of the most sophisticated telescopes ever dreamed up by humanity. It was one of them, a decade and a half ago, that captured the pastel pink tones of the Pillars of Creation.

When it did, however, it did so using three different filters, each corresponding to a different colour of light. Together they span the visible range, meaning their combined image comes close to something our own eyes may see, if the nebula were only bright enough. Light from beyond - the infrared and ultraviolet, radio and gamma - was excluded too, just as our eyes would do.

The pinks of this image come from hydrogen atoms losing their electrons and then regaining them, a process driven by the light of young stars. The darker shape of the pillars comes from the opaque dust they contain, standing out against the light shining from nearby massive stars.

The Eye of Hubble

The most famous image of the pillars, however, is that taken by Hubble, an observatory orbiting hundreds of kilometres above the Earth. From its viewpoint the stars appear as pinpricks of light. They do not twinkle in Hubble’s eye, since up there, above the bulk of the atmosphere, there is no air through which to distort their rays of light.

Thanks to this, Hubble has a sharper view of the pillars, and of celestial objects in general, than any telescope on Earth. It also - thanks to the instruments it carries onboard - can see a wider range of frequencies than the human eye can. Its cameras can see some way beyond red, into infrared, and some way beyond violet, into the ultraviolet.

The famous image it took in 1995 of the Pillars of Creation, then, includes colours we cannot otherwise see. Indeed, just as for the observatory in Chile, Hubble’s image was originally made using three different filters, looking at three different colours.

The first filter, which was coloured red in the final image, showed the light coming from sulphur atoms in the cloud. The second - coloured green - showed hydrogen, and the third, blue, showed oxygen.

But - and this is a little odd - hydrogen is not green, it is red. The colours in the image are thus false colours, and do not represent reality. Our eyes, if they could see the colours themselves, would see a redder scene than that presented by Hubble.

Why was this done? Well, most likely because the sulphur atoms, at least in the frequency observed, also shine in red. To make the distinction between them and hydrogen clearer, another colour was chosen for the latter. That helped bring out details in the image, although at the expense of natural colour. You can see this clearly, by the way, by looking at the stars - which appear an unnatural pink in the image.

Making The Invisible Visible

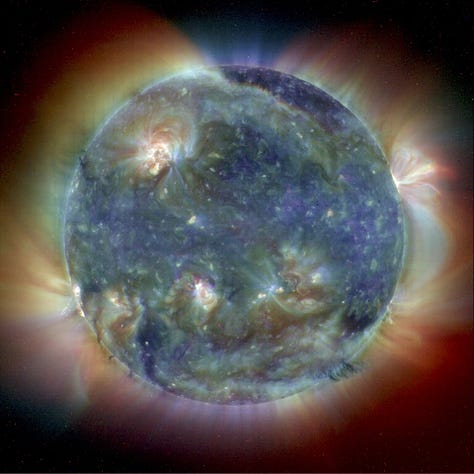

The Earth’s atmosphere doesn’t just distort the light coming from distant objects, it also absorbs it. Many frequencies, indeed, are almost completely blocked by the atmosphere, making it hard to observe them from the Earth’s surface. Only by rising above it, on balloons or on spacecraft, can we get a better view.

As it turns out, the light just beyond red - the infrared - is one of those affected by this block. Building infrared telescopes on Earth is therefore hard - which is a shame, because there are a lot of objects, like planets, brown dwarfs and nebulae, which are a lot more visible and interesting in the infrared than in the visible light.

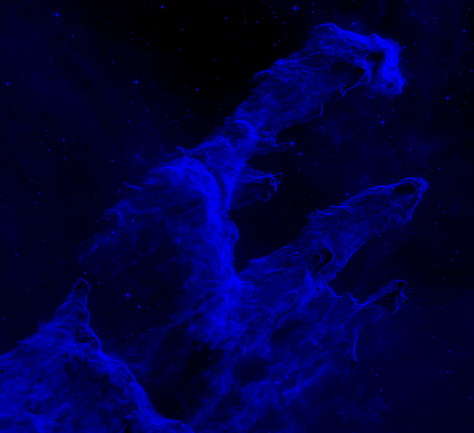

To solve this problem, astronomers have built space-based infrared telescopes. The most powerful of these, of course, is the James Webb, the largest observatory ever placed in space. It is equipped to create sharper images than ever before of the cosmos, and to peer deeper into it than any other telescope.

But - and here is the point - infrared light is invisible to our eyes. We cannot see it, although we might sometimes sense it as a warmth on our skin. Every image produced by the James Webb must therefore use false colours, otherwise we would see nothing of the fantastic data it is sending back.

Its image of the Pillars of Creation, indeed, was originally based on six different filters of infrared light. Each, at first, appeared only in black and white, showing simply the brightness of light recorded. To combine them, image specialists first assigned colours - false colours - to each.

The result, after combining and editing, shows the structure of what the James Webb saw, as well as the relative brightness of different areas of it. The colours are not real, but they do represent colours - different frequencies - of infrared light. False, perhaps, but still not without meaning.

But why do the pillars themselves look so different? In both previous images they were opaque dusty towers, but to the James Webb they seem translucent, almost ghostly in their appearance. This, in the end, is down to the properties of infrared light. It is able to penetrate dust clouds more easily, as X-rays can penetrate our bodies, and so look inside the pillars to show us the stars forming within.

Are these images lies? Well kind of. The colours of astronomical photographs, certainly, are rarely to be trusted, and many objects would indeed look differently if we could see them ourselves. But then this is true of many kinds of photography.

Cameras - whether infrared or not - do not capture the world exactly as our eyes do. Photographers can manipulate the light they see, by using longer or shorter exposure times to capture motion, by brightening things, or by filtering out colours or polarities of light.

Neither do cameras anyway see colours exactly as we do. The filters and sensors they contain differ to those in our eyes, and can often see a little beyond the visible range. Many smartphone cameras, for example, can see infrared light, like that used by a remote control. The images they create are, as well, manipulated by software to make them look more natural.

All images, indeed, are just representations of the world around us, ways to make reality visible. That holds true for photographs, but it also holds true for our eyes and brains. We many like to think the colours we see are true or natural, but they are, in the end, a mere fraction of the reality taking place around us.

I had one of these spectacular red/purple posters in my wall when I was a kid. I bought it at the Griffith Park Observatory. The place the Terminator started his rampage through LA. The poster captivated me then, just as your additional pics and article did now. It's not fake, rather I think it's actually brilliant to try and visualize what our eyes cannot see

Many thanks for this in-depth analysis of the true colors of the images we are shown. Using the Pillars of Creation as an example was brilliant since those structires are shown in almost all our coffee table books. What do the Pillars look like through the X-ray telescopes like Chandra?

Lastly, since we've been looking at these structures since the nineties, is that a long enough baseline for our computers to create a projection of what they will look like in a hundred years, a thousand? a million? Similar to forecasts of weather phenomena, such a video would have awesome besuty.