The Future Is More Terrifying Than We Can Imagine

The horrors of life in a dangerous universe may be beyond our comprehension.

Half a century into its interstellar escape from Earth, the ship Blue Space stumbles across the mysterious ruins of an alien civilization. Strangely, these ruins exist in four dimensions, one more than in our familiar world. Out of curiosity the crew halt their ship, and then make a perilous voyage across higher dimensional space to investigate.

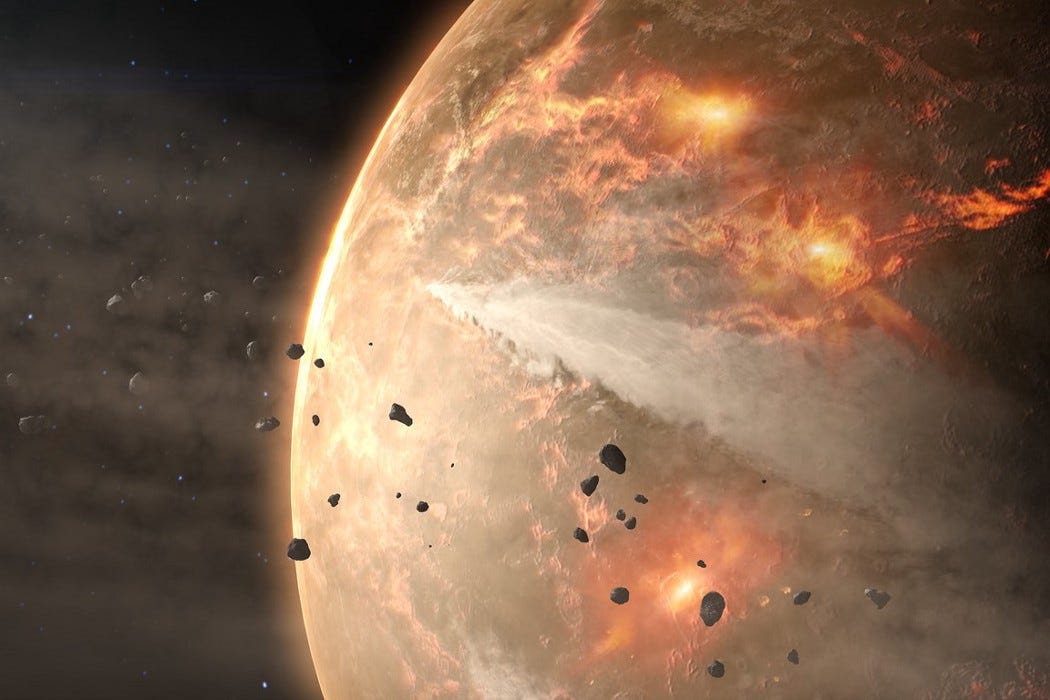

At first the ruins seem impenetrable. But a closer inspection reveals a horrifying truth. These are the tombs of a dead race; and worse, their universe itself is collapsing. The bubble of four dimensional space that Blue Space has encountered is shrinking, falling into three dimensions.

As the ruined marvels of this long dead civilization are consumed by the edge of the bubble they are destroyed, unable to survive in a lower dimension. Before long nothing remains, and a million years of history is gone forever. Shaken, the crew of Blue Space resume their flight, heading deeper into a dangerous universe.

This dark story is told in Death’s End, the final book of Cixin Liu’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy. Technologically advanced civilizations have discovered how to manipulate the fundamental laws of physics, and have used them to create terrible weapons of war. One of these, a weapon that alters the dimensionality of space, has horrifically destroyed the lost civilization encountered by Blue Space.

Since its publication, much attention has been paid to Cixin Liu’s ideas. His Dark Forest theory, the idea that intelligent civilizations should fear each other and conceal their existence, is perhaps the best known concept of his trilogy. But another idea is in his books, one with even deeper implications.

This is the idea that the universe has been shaped by intelligence, much like how the Earth has been shaped by our own civilization. When we look up at the night sky, he speculates, we are not seeing an untouched and pristine wilderness. We are really seeing the result of billions of years of manipulation: an artificial structure on a grand scale.

Is this an idea worth taking seriously?

When astronomers look at the night sky, they try to find explanations for discoveries that are grounded in the known laws of physics. Many things, from supernova to black holes, can indeed be explained in this way. But it is also true that many observations remain unexplained.

We know, too, that our knowledge of physics is incomplete. We lack a complete theory of gravity, for example, and our laws cannot describe the interior of a black hole. In time, some of the strange things we see in the night sky might be explained by a better understanding of nature.

Until then, we sometimes seem to be papering over the cracks. A century ago astronomers noticed that galaxies don’t spin as predicted. They introduced dark matter, usually portrayed a hypothetical but still undetected particle, to explain the discrepancy. Later still, astronomers found that the universe is expanding at a faster rate than expected. They invented dark energy to cover the cracks.

These are big problems, but there are many less well-noticed mysteries. We’ve observed galaxies and stars that are old enough to challenge the Big Bang theory. We’ve encountered bursts of ultra-high energy rays echoing from galaxy to galaxy, again without explanation. Particles from deep space have struck our detectors, moving faster than should be possible. And strange patterns of light have been seen coming from far away stars, sparking speculation of advanced civilizations.

Most astronomers argue that all of these things will eventually be explained by physics, if only we could get better data and uncover the laws behind them. And so it may be. Indeed, other mysteries have often been revealed to be rather mundane, once the right law of physics was known.

Here, physicists often come back to the argument that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. The simplest explanation for what we see is the natural one: that things have evolved without any intelligent intervention. In the absence of any evidence saying otherwise, scientists default to this explanation, even when our current laws fall short.

In essence this is a form of caution. We don’t know the full scope of the laws of physics, and we don’t know all of the different ways in which they may manifest. Without a complete theory of nature we have no idea what the limits of the possible are. We may never truly know what they are.

As a result, we cannot pretend we know the scope of what nature encompasses. Known unknowns like dark energy and dark matter can be accepted for this reason - nature is weird, and probably a reasonable explanation these things will eventually turn up. But until it does, we need to fill a gap in theories, and these dark entities offer a way for science to refine the possibilities.

But at the same time, we don’t know the limits of science. We don’t know how much we don’t know. And as result, we also don’t know the limits of engineering and technology. We have no idea, in short, what an advanced civilization might be capable of.

Yet, for some reason, we like to think we do. Predictions of the future invariably imagine a world based around familiar technologies, only bigger and more powerful. And as SETI showed, we apply this lack of imagination to our conceptions of how alien civilizations might look.

For decades researchers have been scanning the skies for unexplained radio signals coming from the stars. At first glance this is not an unreasonable thing to do. Radio waves were our first form of long distance communication. One can circle the Earth in mere seconds, cross the Solar System in days, and reach the nearest stars within years. If we want to talk to aliens, radio might be the way to do it.

But the results have been disappointing. The astronomers hunting for signals started out optimistically. Back then, at the turn of the twentieth century, we thought life would be common in the universe, and that even Mars would be home to sophisticated beings.

Within a handful of decades, however, these hopes were dashed. The search has found little but silence, and the longer this has gone on, the more our perceived isolation has grown. The conclusion now seems to be that we are alone, at least in our own galaxy.

There is another explanation for the silence. Radio communications are a primitive, wasteful technology. A century after we first mastered the technique, we’ve moved on to better methods. Instead of radio signals, we fire laser beams down fibre optical cables. Spacecraft will soon bounce lasers across the Solar System, transferring gigabytes where radios could only manage kilobytes.

In other words, technology progressed. And though we can’t be sure how alien civilizations might develop technologically, it seems reasonable to think they would stumble upon on the same possibilities we have. Civilizations probably pass through a brief period of radio based communications before moving, like we are, on to more advanced and so far unimagined technologies.

If this is true, then it is no surprise that the hunt for radio signals has come up empty-handed. The astronomers looking for aliens were mistaken: they assumed that the future looked like the present. They thought, wrongly, that alien civilizations, perhaps thousands or millions of years more advanced than us, would use a technology we developed before we went to the Moon.

In this, Earth astronomers are akin to primitive tribes on an ocean island, searching the skies for smoke signals while invisible radio signals fly by.

This mistake crops up over and over again. In one recent example, astronomers took it upon themselves to scan nearby galaxies for signs of Dyson spheres — hypothetical constructions that surround stars with solar panels to extract the maximum possible energy. They found no signs that one was ever built.

But the future is not like the present. A civilization that has the ability to build a Dyson sphere undoubtedly has more advanced and better ways to generate energy. Astronomers hunting for them are making the same mistake the Victorians did, believing that the future would see ever bigger steamships.

The big error in predicting the future is to assume things progress steadily and linearly. Year by year things get a bit better; a bit more efficient. And at times it does - but there is a second way in which we make progress. A sudden breakthrough can rapidly shift paradigms, and offer a previously unimagined way to do things.

Relativity and quantum physics are two examples of this. Both were inconceivable even a decade before their discovery. But both ushered in fantastic new technologies, from GPS systems, to lasers, to the transistor. No one in 1890 could have imagined the world of the 1990s, with its jumbo jets, its interconnected calculating machines, its nuclear arsenal, its plastics, or its robots on Mars.

It is foolish, then, to think we can imagine what life will look like in the twenty-second century, or at the dawn of the fourth millennium a thousand years from now.

In Cixin Liu’s novel, advanced civilizations discover how to manipulate the laws of physics. They use this knowledge to build not only terrible weapons, such as the dimension collapsing one Blue Space encountered, but also defensive structures, which play a key role later in the book.

In doing so, these civilizations gradually shape the nature of the universe. By the time humans venture out beyond the edges of the Solar System, they find a galaxy far removed from its original, natural, condition. Could it be that this same concept applies to the universe we really live in?

In short, we don’t know. We don’t know what the full laws of physics permit. Dimension-collapsing weapons like Liu imagines might be impossible, beyond the realm of reality, or they may be just a century into our future, permitted by some undiscovered theory of nature. But even if they are impossible, other things, so far unimaginable, certainly are.

And so the fact that searches for alien intelligence have so far come up empty handed is almost meaningless. It means only that we have been looking for the wrong signs. Indeed, the right signs may be just in front of our noses, clear if only we could read them or simply imagine them.

This also means we cannot discount Liu’s second and more frightening conclusion: that the universe is a dangerous place, potentially hostile to our existence. The weapons that exist far from Earth are surely dangerous indeed, and as absurd and terrifying to us as the raw power of an atomic bomb would seem to a stone age tribe.

The prospect of these weapons, and of the unpredictable nature of the technological breakthroughs that allows them, drives the narrative of Liu’s triology. And faced with such existential horror, indeed, the only logical action for spacefaring civilization is to hide.

The question for us, is whether the same dark logic holds in the real universe. And if it does, and we live in a galaxy both shaped by intelligence and filled with weapons terrifying beyond our comprehension, we should be thankful we have so far escaped the attention of the stars.

Re: Dyson spheres, I used to be really fascinated by them until real physicists started picking the concept apart. I think it was Neil DeGrasse Tyson recently who pointed out a problem to the effect of, there isn't enough material in the solar system to construct one, so we would already need to have the technology to deconstruct multiple solar systems, but powering that operation would require us to already have a Dyson sphere

I have always felt that while CETI is a worthwhile, albeit likely futile, undertaking, METI is just plain stupid. It is the equivalent of hanging a "Free Lunch" banner on our planet. Unless 100% of all interstellar civilizations, if they exist, are unaggressive, then we are committing an unforced error. 100% universal peacefulness is about as probable as 0%, so, in the fullness of time, the probability of a hostile alien race (again, if any aliens exist) seeing our signal is too high for comfort. These interstellar hippies will be the death of all of us, or at least of our descendants.