The Week in Space and Physics #18

On Europe and Space, the exploration of Venus, Gaia's astrometry and mapping the Moon

Is Europe losing an undeclared space race? That question lay at the heart of a recent interview with ESA boss Josef Aschbacher. Europe, the implication ran, has been resting on its laurels while rival powers – namely China and the United States – rush ahead. Even worse, the continent has tied its fate to Russia, a partnership Europe has now come to regret.

The most immediate problems surround ExoMars: a planned Martian rover that now faces years of delay. ESA had been counting on Russia to supply both the rocket and landing system. Following the outbreak of war in Ukraine, however, the agreement was scrapped. Europe must find an alternative solution – but whatever it is, it looks likely to be many years before it is ready.

In all fairness, though, ESA has notched up several successes in space science. It has landed probes on Titan and on comets, put satellites around Mars and Venus, and has an array of advanced observatories orbiting the Earth. With this background the issues with ExoMars seem to stem from a naive choice to rely on Russia, rather than a deep problem in the way ESA does science.

Bigger questions surround Europe’s commercial potential in space. While China and America race ahead, launching astronauts and building space stations, Europe seems to have barely got off the starting line. The continent has no reusable rocket, nor a clear path to build one; no ability to launch astronauts into space; and no clear plans for what to do after the space station retires.

That’s not to say they aren’t doing anything. In recent years Europe has poured vast sums into new rocket companies: half a dozen or so are now springing up across the continent. That may inspire a European spaceflight renaissance – but rocketry is hard, and little concrete has emerged from the money so far. But just like Europe was slow to realise the potential of new rockets, they now seem to be only tepidly moving towards the next generation of space stations.

As China builds a new and capable station and NASA funds several private companies to build their own, ESA is still thinking about what to do. Tentative plans call for something known as “SciHab”, a small module that would act as a science laboratory in orbit. Yet this is unlikely to be a full station of its own. More likely ESA would once again rely on America, piggy-backing on their commercial stations.

That looks like a missed opportunity. Europe surely has the potential and engineering capability to be more ambitious. A European space station – even better a commercial one – would be a chance to forge a more independent path. It may also – whisper it – give Europe a reason to build up its own astronaut corp. At present the continent has just seven active astronauts, compared to around fifty in America and maybe two dozen in China.

Yet the problems probably run deeper than just ESA. The space agency is beholden to political whims and spending – and Europe has a poor record on taking advantage of new innovations. There is no European Google, no significant cloud computing provider, no equal to Amazon or Ali Baba. Space does not have to be the same – Europe has plenty of potential – but ESA need to grasp the moment, or risk falling far behind.

DAVINCI Prepares For Venus

Venus is a tough place to explore. Soviet probes sent in the 1970s and 80s encountered a hostile world forever covered in thick clouds of sulphuric acid and seared by an awful heat. Few of those probes survived long under such conditions: almost all died within an hour of entering the Venusian atmosphere.

Perhaps little surprise then, that the planet has been ignored in recent decades. Just a handful of probes and orbiters have visited the planet this millennium; nobody has attempted to reach the surface since 1984.

Things are, however, changing. The discovery of phosphine in the planet’s atmosphere a few years ago inspired a buzz of interest in possible life on the planet. A series of exploration missions were soon announced. One of those is DAVINCI, a planned probe that will orbit and monitor the planet’s atmosphere sometime around 2030.

It is DAVINCI’s lander, however, that is sure to draw the most attention. Shortly after the probe arrives at Venus, it is expected to plunge through the planet’s atmosphere. Planners do not expect it to last long: anything more than an hour will be a big surprise. Indeed, they are not even sure the probe will survive to reach the surface. The team instead is focusing on what can be learned as it falls through the layers of cloud.

One key aim for planetary scientists is to understand how Venus became so hostile. Many models suggest the planet was once similar to Earth, perhaps even home to oceans and primitive life. Yet somewhere in the intervening years things went horribly wrong. The planet, unlike Earth, somehow overheated. A runaway greenhouse effect turned Venus into a literal hellscape; a place probably – but not certainly – hostile to life.

DAVINCI will attempt to understand how this happened. Studies of the atmosphere could reveal how it has evolved, and where it came from. They should also unveil the current activity on the planet, such as whether any volcanoes still erupt under those thick clouds. DAVINCI may also be able to answer lingering questions about phosphine – clarifying whether any is really in the atmosphere and, if there is, where it is coming from.

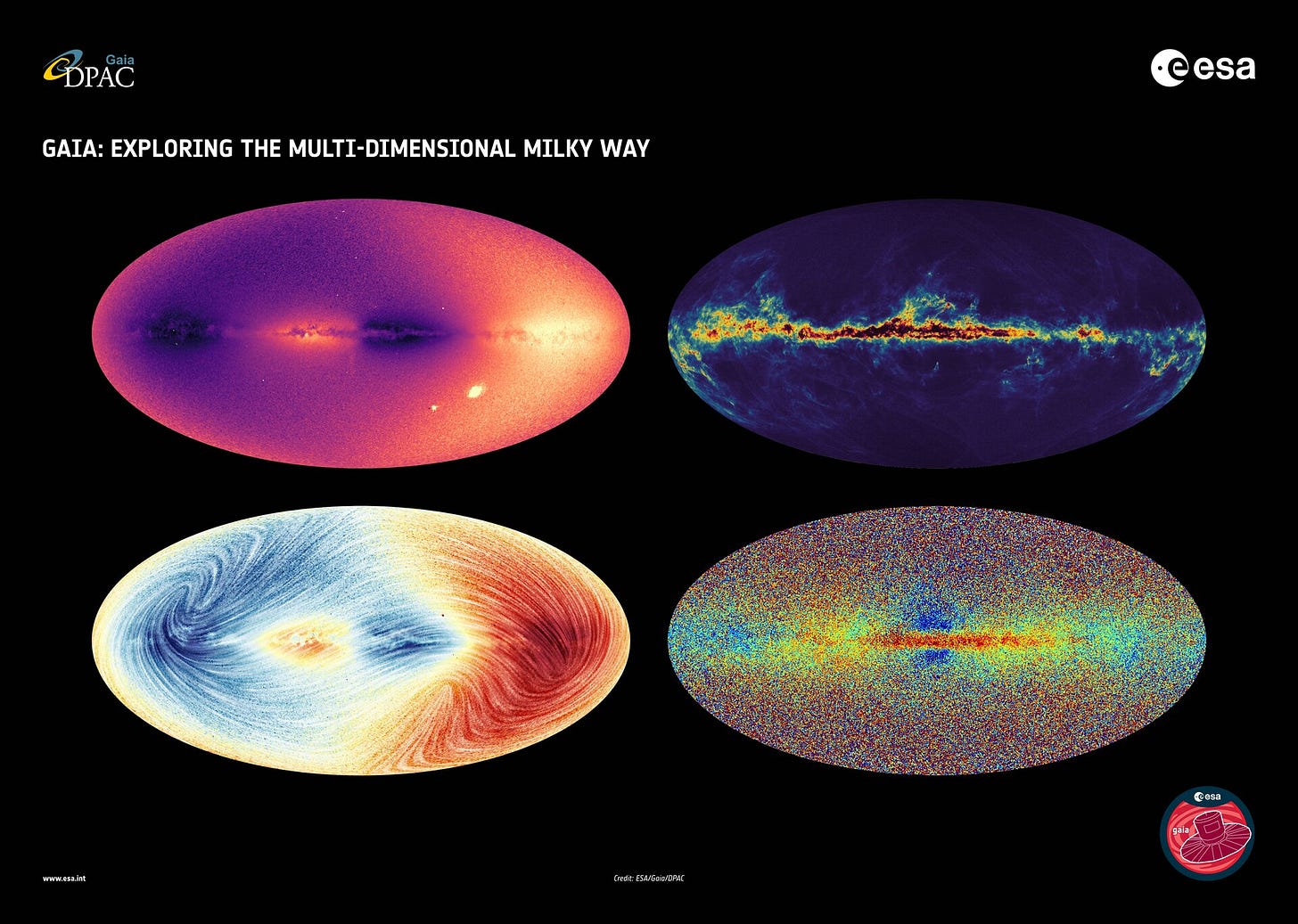

Gaia Maps the Milky Way…

For the last nine years the Gaia satellite has been measuring the positions, distances and movements of millions of stars. This – the art of astrometry – will give us the most accurate map of the Milky Way ever made; tracing the location of a billion stars.

The mission team last week released the third data set from Gaia. It includes details on the temperatures, colours and chemical composition of millions of stars, as well as observations of thousands of asteroids and millions of galaxies. Surprisingly, astronomers also found the telescope could pick out vibrations in the shapes of stars themselves. That revealed so-called “starquakes”, a phenomenon that sees stars shrink and swell.

Gaia’s map of the Milky Way should help astronomers trace back the history of our galaxy. Measurements have already found thousands of stars born in other galaxies: victims, perhaps, of long ago collisions between cosmic giants. Researchers are sure to spend the next few years poring through the dataset, looking for more clues about how our galaxy evolved.

More data releases will follow in the years to come. The next – the fourth – will provide even more accurate data from Gaia’s observations, revealing variable stars, exoplanets and distant galaxies. Another release will – assuming the telescope continues to work for another year or so – provide data from a full decade of observations.

… As China Maps The Moon

A team of Chinese scientists last week published the most detailed map of the Moon ever made. The map charts the location of over twelve thousand craters, traces eighty larger impact basins and plots the geological makeup of the Moon across its entire surface.

There is a hint of geopolitical rivalry in the map – America released its own less detailed map two years ago. Indeed, other maps have been around for a while, though most are regional, focused on well explored regions of the Moon. Through them planetary scientists hope to trace the history of the Moon, learn how key features came to be, and perhaps lay the foundation for future human exploration.

China is taking lunar exploration seriously: it has put several “Chang’e” rovers on the lunar surface and, two years ago, collected samples of Moon rocks for the first time. More is likely to follow. China is already planning a decades long campaign of lunar exploration, perhaps culminating in a manned base in the 2030s or 2040s.