The Week in Space and Physics: A Real-Life Tatooine?

On worlds with two suns, a planet-eating star, rogue planets, and a hint of life far beyond the solar system.

Luke Skywalker, George Lucas told us, was raised on a world with two suns. That made for good science fiction – after all, what could be more alien or fantastic than the sight of two stars setting over the desert landscape of Tatooine? Yet for a long time astronomers questioned whether any such world could exist in reality.

The problem was twofold. First was a question of chaos: the presence of two stars, astronomers reasoned, should disrupt the formation of planets. As the stars swept around each other the forces they exerted on their young worlds would be constantly changing. They might thus rip them apart, or simply fling them out into interstellar space.

Even if they could survive, however, we still had the second challenge of finding them. Our techniques for spotting planets around other suns work best for individual stars and are often confounded by the more complex arrangements possible in binary systems. Aware of this difficulty, for a long time astronomers quietly ignored double stars when hunting for exoplanets.

Over the past decade, however, things have changed. New models have shown that planets really can find stability around binary stars. And better telescopes have found armfuls of them: there are, as of the latest count, more than seven hundred planets known in binary systems. Most of these are “s-type” planets, meaning they orbit only one of the two stars. Yet sixteen are “p-type”, and so orbit both. These worlds are blessed with regular Tatooine-like sunsets.

Last week astronomers reported finding one of the strangest such p-type systems known. It lies about a hundred and twenty light years from Earth, and contains two small faint stars alongside a planet of unknown mass. Unlike most other systems, this planet orbits over the poles of the stars and so moves in a plane perpendicular to that of its two suns.

Though the stars are young – neither is older than fifty million years – it seems unlikely the planet could have formed in such a strange orbit. Instead it probably started out orbiting on more or less the same plane as its stars, before an encounter with some other star knocked it off course and sent it soaring over and under the poles.

Even rarer is the nature of the two suns. In truth, indeed, neither quite qualify as stars. They are instead brown dwarfs, a kind of halfway point between planets and stars which lack the mass to sustain nuclear fusion and so to shine as stars do. These objects are cold and dim and hard for our telescopes to see. And although they are probably common, few brown dwarfs are known. Even fewer are known in binary pairs like this, and none other has such a strange orbiting planet.

Sadly, however, it is unlikely anyone is watching the twin sunsets of this world. The brown dwarfs are too cold to sustain life on this planet, and too faint to be easily seen from its surface.

The Star That Ate a Planet

In 2020, telescopes picked up a strange event happening some twelve thousand light years away. It looked, at first, like a star had suddenly brightened, shining a hundred times more strongly than before. Over the following weeks it slowly faded, and after about six months it was more or less back to where it had started.

Normally when stars brighten like this, they also heat up. Oddly, however, measurements showed this star to be accompanied by a set of molecules that can only exist at low temperatures. Even more strangely, the star was seen to shine brightly in infrared wavelengths, probably, astronomers thought, because it was throwing out clouds of cold dust.

Put together, this seems to suggest the star collided with another. Yet if it had, calculations suggested the initial flash would have been far brighter. Instead, then, the watching astronomers came to another conclusion: the star had consumed a large planet, one a few times heavier than Jupiter. The flash of light was the planet falling into the star, and the cloud of dust was thrown out in the aftermath.

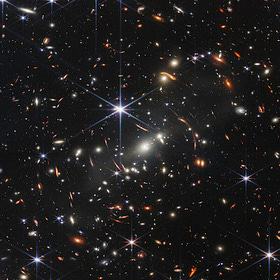

The first studies on this were published in 2023. Afterwards, astronomers directed the James Webb Space Telescope to examine the star in detail. What it found astonished them: instead of the star expanding to engulf the planet, as they had expected, the planet itself seems to have slowly spiralled inwards until it crashed into the star.

Most likely, they say, the giant planet spent millions of years slowly moving closer and closer to its star. As it began to enter the outer layers of the star it would have fallen faster, smearing out into a long tail and then blasting away a cloud of cold gas and dust when it was finally consumed.

Webb also revealed more evidence that a giant planet really was involved. It found traces of carbon monoxide and phosphine around the star, both molecules that are often found in gas giants. All this, they say, is a clear sign we have seen for the first time what happens when a planet falls into a star.

How Many Rogue Planets Are There?

Not all planets orbit stars. Some are lost, doomed to spend an eternity floating in the cold void of interstellar space. Indeed, some models suggest our own solar system once had a fifth gas giant. This planet, they say, was expelled by a long ago bout of gravitational chaos, and has ever since roamed the galaxy alone.

In recent decades, we have found a few of these rogue planets. But most are invisible, being too cold and dark for our telescopes to spot, and thus the true number of rogues out there is unknown. It is, however, possible to make a guess.

To do this, a recent study looked at how planets interact as a solar system is born. There is no guarantee they form in stable orbits. Indeed, sometimes planets crash into each other – this might have happened to Earth long ago, and the debris from the impact might have formed the Moon. Others are pushed outwards, and forced to drift ever further from their stars until they are lost altogether.

These two scenarios, the study says, are far likelier than we had thought. Planets should collide in roughly four out of every ten young solar systems, they say, and each system will lose on average three planets in their first billion years. That adds up to a lot of lost planets out there.

Hints of Life?

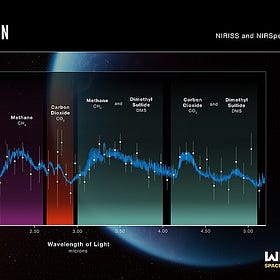

A team led by the astrophysicist Nikku Madhusudhan reported finding strong evidence of the gas dimethyl sulphide around the exoplanet K2-18b. Since this gas is mostly produced by marine life on Earth, he reckons this discovery could be the first sign of life beyond the solar system.

Madhusudhan thinks K2-18b is what he calls a “hycean world”, that is, a planet a few times more massive than Earth with a thick hydrogen atmosphere and a deep warm ocean. In theory such a place could be habitable, and if it is, that life might create gases like dimethyl sulphide.

Yet other researchers have their doubts. There is no proof of water or oceans on K2-18b, they point out, and neither is there any certainty that the dimethyl sulphide is being made by living creatures, or even that it is there at all. For now, as The Quantum Cat covered last week, K2-18b remains an intriguing place, but not yet one we can say is home to alien life.

Read More

The James Webb Still Hasn’t Found Life on K2-18b

A year ago, rumours surfaced of an impending discovery of alien life. They focused on the planet K2-18b, an intriguing wor…

Things Are Bigger Than We Imagine: On the Hidden Threads of Creation

There was a time, long ago, when we were conceited enough to believe the Earth and humanity lay at the centre of creation. Kings and emperors proclaimed themselves the rulers of the universe, and thought they alone somehow held sway over the stars and planets.

Did We Invent Mathematics? Or Did We Discover It?

The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of foot…

The section about planets with multiple stars, and the one about a planet crashing into its star, both made me thing of the Liu Cixin trilogy ("The Three-Body Problem"). The aliens' planet is part of a three-star system (an imagined version of the Alpha Centauri system), and chaos is very much a part of the picture.