The Week in Space and Physics: Looking for Water on Venus

On the search for Venus' ancient oceans, spying stars beyond our galaxy, a second big bang and the launch of Proba-3

Until the 1960s, it was still possible to believe Venus might be a lush and tropical planet. Some imagined it to be covered in tropical jungles and home to wild and savage beasts, much like they imagined Earth had been in the age of dinosaurs. Others dreamed of vast oceans, stretching across the planet and feeding the deep endless clouds that envelope Venus’ skies.

The truth was rather more ugly. Measurements of its atmosphere saw no signs of life or of oxygen. It was in fact dead, made mostly of carbon dioxide and filled with clouds of sulphuric acid. Radio measurements found Venus to be incredibly hot, so hot that no water could possibly exist on its surface.

Yet this harsh reality did not quite kill the idea of oceans on Venus. True, such things are impossible today. But turn back the clock billions of years, to a time when the solar system was young and Venus had not yet suffocated under a toxic atmosphere. Back then, some climate models hint, Venus might have held deep oceans, just as Earth and Mars did.

Those oceans could have lingered for millions of years, fueling a cycle of weather on Venus somewhat like the one we have today on Earth. But then things went drastically wrong. Intense volcanic eruptions triggered wild global warming, and in the resulting heat the oceans first evaporated and were then lost into space. Venus dried out, and remains as a cautionary tale of how planets can be irreversibly damaged.

Not everyone agrees with this story. Other climate models say Venus has always been too hot to have deep oceans, and any water it once had must have been quickly lost. If so, Venus probably gained its current atmosphere soon after it formed, and it has remained relatively unchanged ever since.

To try to answer the question, a group of researchers at Cambridge University recently looked for signs of any ancient water. If oceans ever existed on Venus, they say, then some part of them must remain on the planet, locked inside rocks and buried under its surface. We cannot detect that water directly, of course, but volcanic eruptions could offer a way to trace its presence.

Logically, eruptions would release some of this water. That, in turn, would leave a chemical signature in the atmosphere - one that we should be able to find, even if we cannot find the water itself. And indeed, when the researchers modelled the expected chemical reactions in Venus’ atmosphere, they concluded that they could see signs of water being emitted.

But they also found that the amount of water is low. The interior of the planet, they say, is therefore likely to be dry. Certainly there is not enough water still around to support the idea of an ancient ocean on Venus.

Still, the debate is likely to go on. Not everyone is convinced their assumptions are correct, or that they have accounted for all the processes driving the planet’s atmosphere. That means the question is likely to stay open until we get more data in the 2030s. Three missions are hoping to reach Venus then - two from NASA, Veritas and Davinci - and one from Europe - EnVision.

Spying a Star Beyond Our Galaxy

The largest star known to humankind lies about one hundred and sixty thousand light years away in the midst of a nearby galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud. It is enormous: were it placed in the centre of our solar system, the outer edge of this star would extend far beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

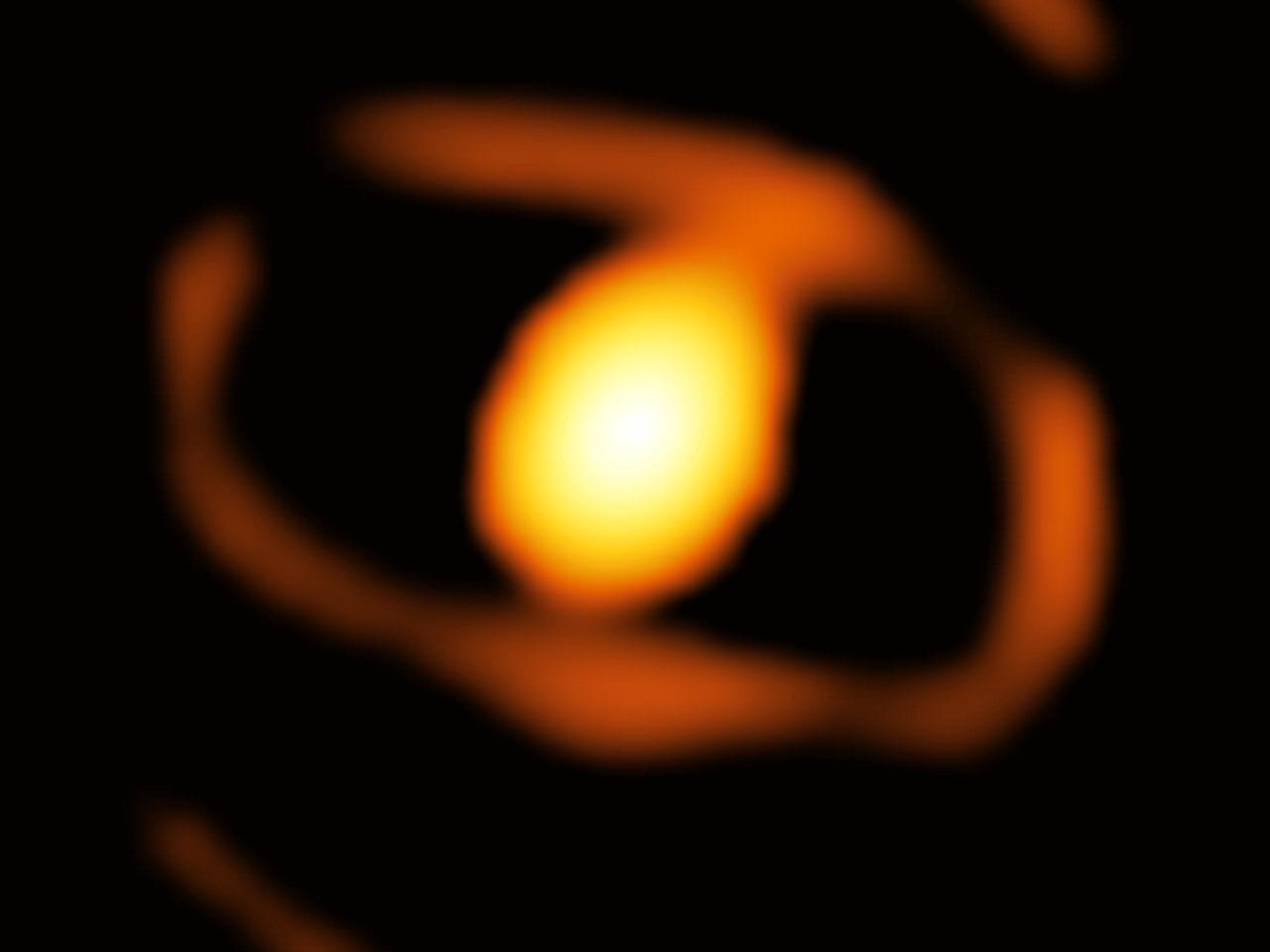

The star, named WOH G64, can only maintain this behemothic size because it is dying. It is a red supergiant which, as its inner core shuts down, is starting to lose its grip on its outer layers. They are cooling and expanding, making the star swell and turn redder. Within the next few thousand years this will come to a dramatic end: WOH G64 will explode, shine brightly in the night sky for some months, and then fade slowly away.

Since WOH G64 and its special status was discovered in 1986, telescopes have kept watch on the star. They have seen it seem to fade in brightness and, in the past few years, change colour. Now, with the help of the Very Large Telescope in Chile, observers have managed to take a close-up photograph of the star for the first time.

What they found shows a star surrounded by a shell of gas and dust. This, they say, confirms WOH G64 is now in the final stages of its life. It also explains why the star appears to be fading: as it draws closer to the end, WOH G64 will go on throwing out clouds of dust, thickening the shell around it and causing the star’s light to slowly fade away. The star itself will also shrink - and so, if it hasn’t already, lose its title as the largest known star.

None of this means the star will explode soon, at least as we humans understand the term. Dying stars can go on shedding gas and dust for millennia before the inevitable supernova comes. Whenever it does happen, however, it promises to be spectacular.

Looking for a Second Big Bang

The Big Bang theory tells us that all the matter and energy in existence was created together at a single moment in time. There is a fair amount of evidence in support of this idea, and so most researchers can reasonably argue that the Big Bang really did create everything.

But this evidence, some scientists pointed out last year, only tells us about the visible matter in the universe. The dark matter - the invisible kind that seems to hold galaxies together and shape the long evolution of the cosmos - could have been created much later. We don’t actually know much about this dark matter at all, they argued, and so there’s no evidence to say it even came from the Big Bang at all.

Perhaps, they went on, dark matter appeared later on, possibly in a “dark big bang” of its own. If so, evidence of this event might linger in the form of gravitational waves. Such waves could even be detected, thus offering a way to test the idea that dark matter was born separately from more normal matter.

In a more recent study, a separate team of researchers took a closer look at the idea. The idea of a dark big bang is surprisingly feasible, they say, and does not contradict what we already think we know about the early universe. Even the gravitational waves might already be visible to sensitive detectors - and so an examination of their data could soon reveal whether the idea is true or not.

Perhaps. The idea is obviously speculative. Nothing about dark matter really hints at a separate creation story, even if nothing rules the possibility out either. But then again, nothing much about dark matter makes sense. Every search for a particle has come up empty handed and time is clearly running out for more sensible theories of the stuff. Why not speculate, then?

Proba-3 Lifts Off

An Indian rocket launched a pair of European satellites yesterday, marking the start of operations for the Proba-3 mission. Over the coming years these two satellites will fly together in a close formation and regularly align themselves to create artificial eclipses far above the Earth.

This will give scientists the opportunity to study the rarely seen outer atmosphere of the Sun. Most of the time this region, known as the solar corona, is drowned out by the bright light coming from the Sun itself. But with Proba-3 researchers will be able to block the disc of the Sun and its light for hours at a time, thus making the corona visible to one of the two satellites and so offering a chance to study it in detail.

The satellites will also demonstrate the art of close formation flying. In order to create eclipses, the satellites must position themselves precisely so that one satellite - known as the occulter - hovers perfectly in front of the Sun as seen by the other. Such formation flying in space is tricky to pull off, and so the mission aims to perfect the techniques required.

Proba-3 is also a special mission to me - I spent about a year working on it - and I’ll be taking a much closer look at the mission in next week’s newsletter.

Curious about relationship between ESA’s different projects. For the development of Probe 3 precision maneuvering systems, was there any overlap with LISA mission (where 3 satellites will fly in precise formation)?

Congrats on Proba 3!

I’m so out of touch of sciencey stuff that I’m not sure how many people work on certain projects like that, but it’s a super cool feat to have something you influenced go into SPACE and bring back info!

Thanks for this installment it was great.