The Week in Space and Physics: The Future of Particle Physics

On charting a future path for particle physics, the secrets of Bennu, our local supermassive black hole and a dream of Enceladus

Two decades ago the future of particle physics looked bright. Scientists had just got their hands on a shiny new machine - the Large Hadron Collider - and were predicting it would soon unleash a wave of new particles and forces. Washed up with that wave would be a new theory of nature - something with a name like string theory or supersymmetry, perhaps - and it would help clear up everything from the mystery of dark matter to the origin of the universe.

At first things seemed to be going well. In 2012, only two years after it started work, researchers at the collider found the long sought Higgs Boson. Soon afterwards hints of another new particle emerged, one hitherto unknown to physics. It might, some said, turn out to be the discovery of the century. In the end it proved to be nothing - the “particle” was nothing more than a statistical blip, and when more data arrived it simply faded away.

The years since have seen that story repeated time and time again: a wave of excitement, a wait for more data, an inevitable disappointment. The Large Hadron Collider has found no signs of new physics, and thus no answers to the big questions troubling modern physics. It has, some now say, failed; though such a word may be too harsh for a machine that has, at least, validated our theories of physics over a wider range of energies.

The question now is what to do next. Building machines to collide particles at ever higher energies is expensive business. A successor to the Large Hadron Collider will cost tens of billions of dollars and consume the work of a generation of physicists. Success is by no means assured: in the worst case such a machine would waste half a century of effort and wreck the reputation of particle physics.

In December the American Particle Physics Project Prioritization Panel (P5) released a report outlining a path through the next decade. America should not try to build a big new collider, it says, but it could instead support efforts to construct one in Europe or Japan. Efforts at home should instead be directed towards researching new collider technologies. One day, it says, such work could pay off in a new facility built on American soil.

That might take the form of a muon collider; a concept that seems to be getting increasing support from the physics community. The muon, a heavier sister of the electron, could help achieve efficient high energy collisions at low cost, at least in theory. But muons are also short-lived, which makes them hard to work with. For now, then, American research will be directed towards proving the technology needed to build a muon collider.

Eventually a muon collider could offer a better way forward than another traditional collider. It could be built for a lower price tag, and so let us push the frontiers of physics without betting half a century of progress on one big machine.

The Past, Present and Future of Bennu

Today the asteroid Bennu measures about five hundred metres across, weighs several million tonnes and spends its days drifting between the orbits of Mars and Earth. One day, but not for a century at least, it might smash into one of those two planets, ending its life in dramatic and devastating fashion.

Eight years ago we sent a spacecraft to take a closer look at the asteroid and then bring a bit back for scientists to study. All that went well. The probe, OSIRIS-REx, spent two years examining Bennu and then, last year, delivered a sample of asteroid material back to Earth.

Although the sample was small - slightly more than one hundred grams arrived - it was enough for scientists to start delving into the past of Bennu. They have uncovered a surprising story of ancient oceans and long ago supernova.

Bennu, they think, was once part of a far larger world. This planet, or more accurately proto-planet, formed soon after the solar system was born. At times it must have been covered in a sea of some kind, since the sample includes materials that normally form in warm water. Some of the sample grains look like those found near tectonic rifts on Earth, hinting that the world was also geologically active.

The early solar system might have been full of small bodies matching that description. A few of them live on in the form of moons, but most have long since been lost. Some would have plunged into the gas giants, or smacked into a larger rocky planet. But others must have been ripped apart by gravitational forces, and their remains scattered in space. Those remains, today, would probably look rather like Bennu.

Other grains seem to have a more exotic story. Several show the chemical signatures of ancient supernovae and other long dead stars. As such, they may reflect the makeup of the cloud that formed our solar system. Such clouds often absorb debris from dying stars, and sometimes collapse into new stars when buffeted by the shockwaves of nearby supernovae. Our star, and so our planet, may owe its existence to just such an event.

Our Magnetic Black Hole

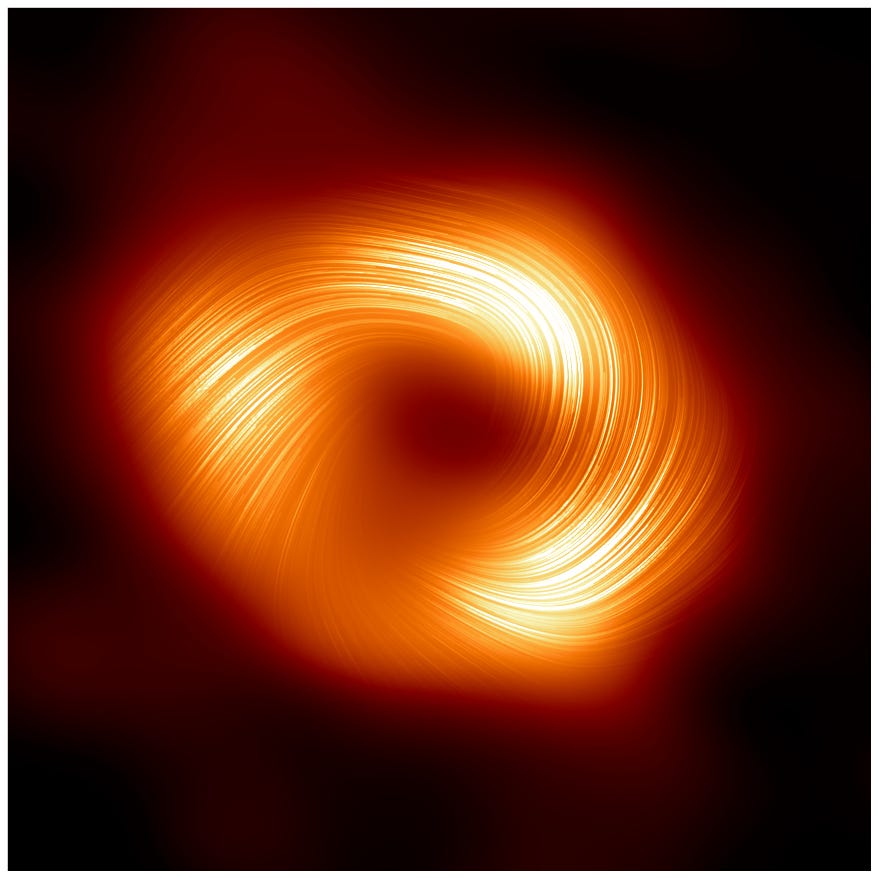

Back in 2019 the Event Horizon Telescope published an image of M87*, a supermassive black hole in a nearby galaxy and the first to be photographed. Then, in 2022, the telescope did the same for Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of our own galaxy. Now it has gone a step further by releasing an image of the magnetic field swirling around Sagittarius A*.

Although black holes themselves are not magnetic, the clouds of debris falling towards them often are. Intense fields can form in those clouds, created as charged particles move rapidly around the black hole. Those can in turn create jets of energy and matter, sending vast plumes shooting out as seen in the spectacular Centaurus A galaxy.

As light moves through those magnetic fields it becomes polarised. That allowed the Event Horizon Telescope to trace their presence, and thus to “photograph” the field around Sagittarius A*. Indeed, this was not the first time the telescope has accomplished such a thing: in 2021 it created a similar image of the field around M87*.

Though the two black holes differ considerably in size - M87* is a thousand times heavier than Sagittarius A* - the images show striking similarities. Both black holes have strong, structured magnetic fields. Both, too, look like they are capable of sending out strong jets of energy. M87* is known to do this, but, so far at least, no such jet has been found in our own galaxy.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t one. Our black hole is relatively calm, and so any jet it is sending out might be faint and hard to see. The new image hints at its presence, but more work will be needed to either find it or rule it out.

Europe Looks to Enceladus

Europe’s space agency wants to take a closer look at the icy moons of the outer solar system. Top of their list is Enceladus, the sixth-largest moon of Saturn and one that likely holds a vast ocean of water under its frozen surface.

Past missions to Saturn have seen geysers of salty water shooting out from Enceladus’ poles, coming from ice volcanoes erupting on its surface. Analysis of that water has revealed an interesting mix of chemicals, including phosphorus, that hint at the possibility of life. If it exists, that life spends its time swimming through a vast warm ocean buried under an icy shell at least a dozen miles thick.

In the proposed mission, Europe would send a probe to land near the southern probe of Enceladus. There it could take a closer look at Enceladus’ ice volcanoes, study the chemicals coming out of them, and scan the surface for hints of life beyond Earth.

Thank you! If I understand Weinstein correctly, he seems to also be suggesting that the promotion of string theory by government funding is deliberately designed to neutralize physics. The motivation Weinstein is suggesting is to prevent new fundamental discoveries in physics (time travel, endless free energy, etc.) from over-turning the apple cart of the existing status quo the way the Manhattan Project did. Do you consider Weinstein’s hypothesis far-fetched?

Thank you for this report on particle physics! What do you think about the contention of Eric Weinstein that string theory is a sterile dead end and that physics has lost its way?