The Week in Space and Physics: The Aurora on Other Worlds

On photographing the aurora, proposed budget cuts for NASA, the next decade of China's space exploration, and ice around distant stars

Every attempt at photographing the aurora borealis, Sophus Tromholt wrote, had failed. That was a shame. The year was 1882, and Tromholt was on a quest to pry open the secrets of the northern lights. His earlier work had revealed the great altitude of the displays – the aurora, he had found, shone at an average height of no less than one hundred and fifty kilometres. But the cause of them was still unknown, and to investigate that he had to go north.

So it was, then, that the summer of 1882 brought Tromholt to the northern coast of Scandinavia. There, armed with a grant from J.C. Jacobsen, the founder of the Carlsberg brewery, he set up a small research centre and started taking measurements of the northern lights. But his attempts at photographing them, as he later wrote, were disappointing.

Even the longest exposures came up blank. No matter what kind of photographic plate or technique he used, the aurora remained stubbornly elusive. Determined to create at least some record of the displays, he turned to pencil and created some wonderful sketches of the northern lights. But later, to his surprise, it turned out his camera actually had captured the aurora on one single occasion, after an exposure lasting more than eight minutes. This photograph – the first ever taken of the northern lights – has sadly since been lost.

In time camera technology improved, and photographing the faint shimmering lights of the aurora became easier. Carl Størmer alone is said to have taken more than a hundred thousand photographs of them, an effort that led him to discover auroral displays at the enormous altitude of one thousand kilometres.

All of these photographs capture the interaction of solar particles and the Earth’s atmosphere. A fluctuating wind of these particles blows over our planet, and as it does the Earth’s magnetic field channels them towards the poles. When they collide with atoms in the upper atmosphere they create lights, and these shimmer as disturbances move through the magnetic field.

Today we have photographs of the aurora from above. Astronauts have seen them glow from the International Space Station. Satellites have captured them from orbit. We have even seen them on other planets: aurora have been photographed around the poles of Jupiter and Saturn, and above Venus and Mars.

Now, for the first time, we have a photograph of the aurora from the surface of another world. In March, as a solar storm swept over Mars, a camera on the Perseverance rover snapped a picture of the Martian skies glowing green. It is not, to be fair, a great photo. There was a haze of dust in the air, and the moon Phobos was shining brightly in the sky, but the green does seem to be there, and, as with Tromholt’s work more than a century ago, it represents a starting point.

Other aurora have been seen in the past by satellites around the red planet. But none of these would have been visible to human observers: the light these satellites detected was strongest in the ultra-violet, beyond the range of our eyes. The colours seen by Perseverance, however, are visible to the naked eye, although the aurora of March may have been too faint to be easily seen.

Future visitors to the surface of Mars might then one day marvel at the sight of these coloured lights glowing in the skies. Some day, indeed, they might just send back the first photograph of an aurora taken by a human on another world.

A Budget Cut for American Astrophysics...

In the coming decade, NASA has plans to launch a big new telescope, send spacecraft to bring back rocks from Mars, and to fly a probe through the atmosphere of Venus. All of these, Donald Trump’s latest budget proposal says, should be cancelled.

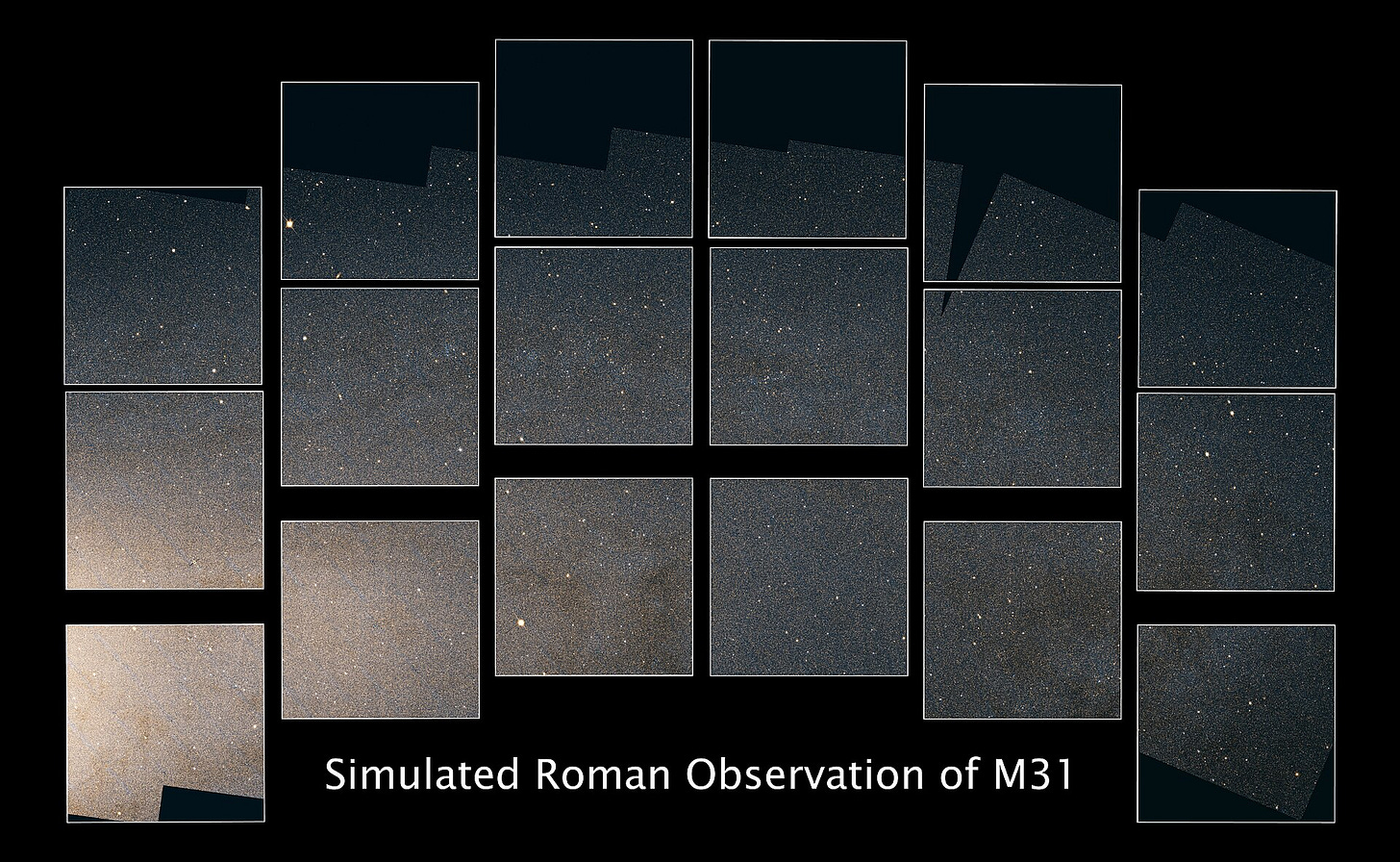

The proposal cuts NASA’s overall budget by almost a quarter, but is particularly harsh on its science activities. Spending on astrophysics would fall by two thirds, to just five hundred million dollars a year. That would be enough to keep Hubble and the James Webb operating, but it would mean the cancellation of the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope.

This would be a huge loss for astronomy. The Roman telescope is designed to create images as sharp as those taken by Hubble, and is equipped with instruments to view wide swathes of the sky. Astronomers were hoping the observatory would capture the first direct images of planets around nearby stars when it launched next year. Instead, it may now be scrapped.

Other cuts will hit efforts to explore the solar system. NASA would likely abandon plans for future missions to Mars and Venus, and probably scale down existing missions. That includes support for the Voyager probes and the older rovers still operating on Mars. Given the limited funds available, NASA would be unlikely to start work on any other new and ambitious projects.

Alongside these cuts, the budget proposal also hits human spaceflight. Reduced funding for the space station means NASA will cut the number of astronauts it sends to work on the station. Each astronaut will also spend more time on board – up to eight months instead of six. The Artemis programme will come to an early end, and with it, the Gateway station, SLS rocket, and Orion capsule will all be scrapped.

Without credible alternative plans – and so far there are none – that would put an end to any hopes for a sustained American presence on the Moon in the 2030s. Indeed the very possibility of an American return to the Moon, or even any American human spaceflight after 2030, is now in doubt.

America and NASA badly need a better plan for their future in space. This, however, is not it.

...As China Pushes Ahead

Even as America seems determined to pull back from exploring the planets, China has plans to make a giant leap forward. According to a recent presentation by the country’s Deep Space Exploration Laboratory, China will send probes to four different planets over the next decade and a half.

Two missions will focus on bringing back samples from Venus and Mars. One, targeting a launch in 2033, will fly through Venus’ atmosphere, capture particles from its clouds, and then return them to Earth. Another, Tianwen-3, scheduled for launch in 2028, will send a series of spacecraft to Mars to take samples from its surface, lift them into orbit, and then fly them back to Earth. Either mission would be groundbreaking. Indeed, no nation has yet obtained samples from either planet.

China also hopes to begin its exploration of the outer solar system. Plans seem firmest for Tianwen-4, a probe that could reach Jupiter by the mid-2030s. Although the overall mission architecture is still unclear, China’s research agency seems keen on studying Callisto, the second-largest of Jupiter’s moons.

After that, the presentation revealed a possible mission to Neptune. That planet has never been explored in depth. Our only visit, indeed, came when Voyager 2 briefly flew past in 1989. Part of the reason for that is the great distance of the planet: what we know about China’s plans suggests the probe will only arrive in the late 2050s.

Alongside these missions, China will maintain and build upon its lunar exploration programme. That will certainly include an attempt at making a crewed landing. Officially, the country intends to put astronauts on the surface of the Moon within the next five years.

Water Ice Around a Young Star

Crystals of water ice are often seen in our solar system. They appear in the rings of Saturn, on comets, and in the outer regions of the Kuiper Belt. Now, for the first time, astronomers have seen them in a disc of debris around a young nearby star.

The observations, made with the James Webb Space Telescope, confirm a long-held suspicion that water ice is common around stars. And, as in our own solar system, the ice crystals observed are not pure, but are instead mixed with grains of dust.

Probably, the researchers say, these crystals were left behind after larger icy bodies – think comets or small, planet-like objects – collided and released clouds of debris. That might mean we are seeing something similar to the Kuiper Belt around our own star – or, at least, to how it was a few billion years ago when the solar system was still young.

Once while camping in northern Saskatchewan, we had the aurora directly overhead. That was the usual "curtain" type, and it was like being a tiny ant looking up at a glowing theatre curtain. The most amazing display I ever saw was back in the mid-1980s outside my apartment in Saint Paul when the whole sky was filled with moving colors. It was almost scary but mostly breathtaking.

Some science fiction (e.g. "Blade Runner" and "Firefly") has pictured a future where China is a dominant force — in some cases, more dominant than the USA. It seems P47 is down with this idea and trying to make it happen. If he persists, the USA will become a second-world country.

sad to read about budget cuts at NASA...i had an internship there back in the early 1990's and that was similar to the reason given for not hiring me when i graduated :-( however, just because NASA isn't getting funded to explore, does that mean we (the usa) won't be exploring other worlds? there's a certain new city in texas that seems to be shooting a lot of rockets off...