How Gaia Mapped The Milky Way

On Gaia, the Tabula Rogeriana, and how we are building the first true map of our galaxy.

In 1138, the Ceutan geographer al-Idrisi set out to map the world. This was no easy task. Few maps of any practical kind then existed, and those that did depicted more dragons and demons than coastlines and cities. Only seafarers had charts of any accuracy, but even these were fragmented and limited in scope.

Al-Idrisi would surely have been familiar with those navigational charts. He had, after all, travelled widely by the time he started working on his map, embarking on journeys that took him across the Mediterranean, along the Atlantic Coast, and even to the towns and cities of the British Isles. By the time he arrived in Sicily in the 1130s, he was about as well-travelled as a man of the twelfth century could be.

And it was armed with that knowledge, and at the behest of Roger II, King of Sicily, that he started work on his map. The task took him almost two decades, during which he sought out the maps of Ptolemy, studied Arab descriptions of trade routes and roads, sent envoys to distant ports, and interviewed every traveller he could find.

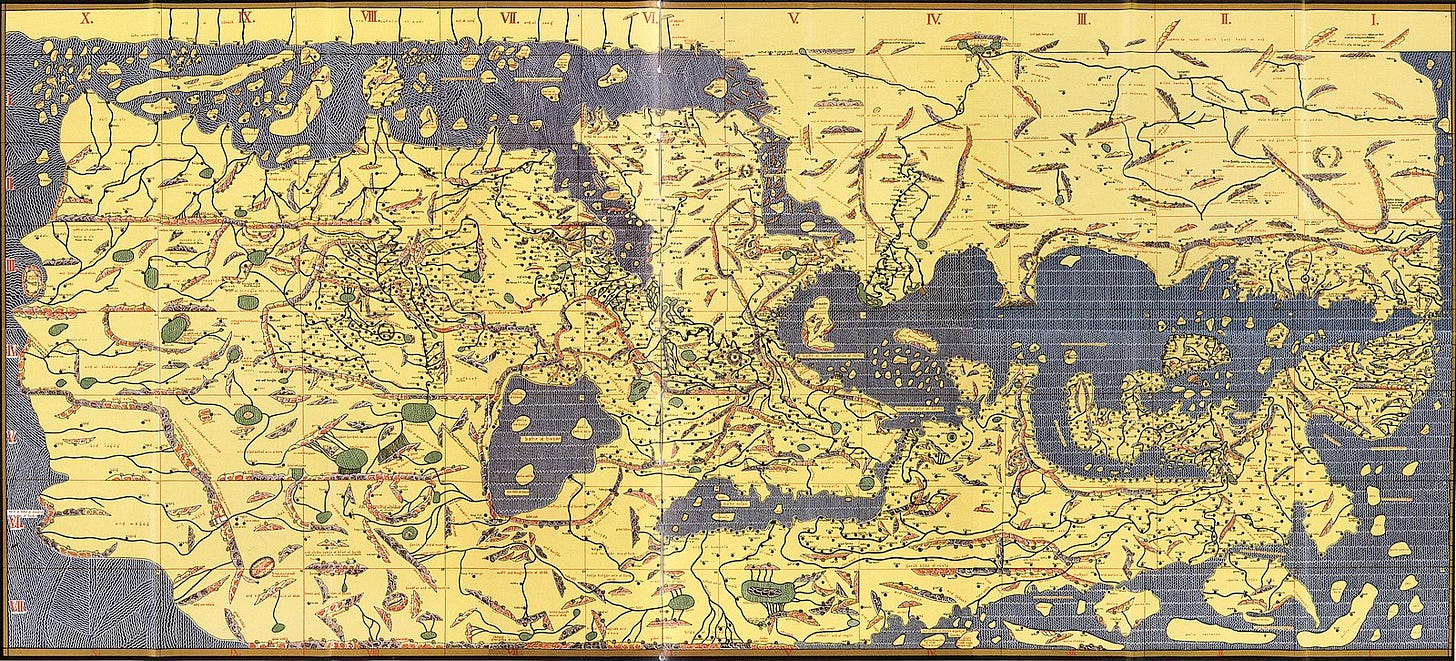

The result was a vast atlas of the known world, collected in a book known as the Tabula Rogeriana. To modern eyes, familiar with our own view of the world, the complete map can seem a little disorientating. Sicily and Italy, the lands of Roger II, appear comically large. The British Isles are shown as nothing more than a vague blob of land. Asia becomes increasingly distorted the more east you look; and even the familiar directions are reversed: in Al-Idrisi’s map south is placed at the top.

Yet there are no dragons on this map. And in places, indeed, he was impressively accurate. The lakes of the river Nile are numbered and positioned more or less as later explorers found them. In accompanying notes he recorded such far-flung places as the coast of Greenland, the trade routes of China, and the Korean peninsula. In one text, he describes a place that sounds very much like the Sargasso Sea, a stretch of the Atlantic lying far closer to the Americas than to Europe.

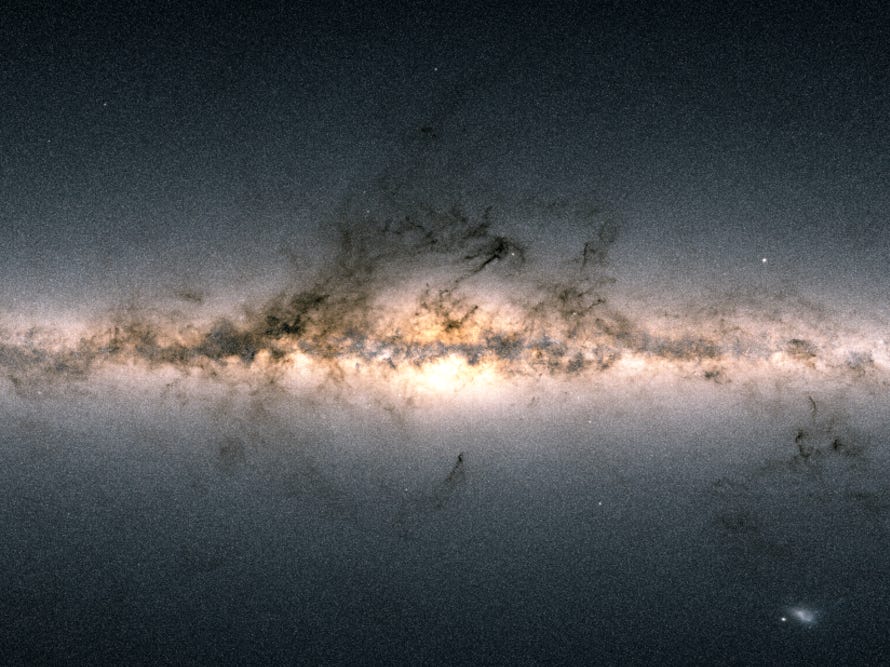

Eight and a half centuries later, in 1993, a pair of Europeans, Lennart Lindegren and Michael Perryman, set out on another audacious map-making enterprise. This time their target was not the continents, not even those unknown to al-Idrisi. Instead they wanted to chart out the stars, recording the positions, colours, and speeds of millions of objects scattered across the Milky Way. The result would be a map, a vast atlas of the galaxy, and one, they hoped, that would banish the dragons from our still poor understanding of its contours.

Like al-Idrisi, they would need to go to enormous efforts to produce their grand map. They would need to rise above the atmosphere, send an instrument to a point one million miles distant, and beam back enough data to fill the greatest library ever built1. Sketching out this plan would take them a decade, collecting the data would take another, and compiling it all into a single vast atlas will consume a third. Banishing the dragons, as it was for al-Idrisi, is the work of a lifetime.

Star Maps and Parallaxes

Of course, in a way, this star map is nothing new. People have been mapping the stars for millennia. In one of the earliest known texts, the MUL.APIN of ancient Babylon, scribes recorded the positions of seventy bright stars, each used for keeping track of the passing year. Hipparchus, in 129 BC, attempted to map the entire night sky, and though his work has been lost, copies of another ancient star catalogue - the Almagest of Ptolemy - still survive.