Hubble: Thirty-Five Years of Stunning Photography

On the first thirty-five years of the Hubble Space Telescope

First, I’d just like to share a call from Dr. Larry Krumenaker to help give the recently discovered ashes of the science writer Willy Ley a well-suited memorial. You can find more details and ideas of how to help in his most recent newsletter.

Last week Hubble celebrated its thirty-fifth year in orbit. It is a remarkable achievement. Indeed, it would be a milestone worth celebrating for any spacecraft: there are precious few, aside from the Voyagers and a handful of mostly defunct satellites, that are still sending back any useful data at all after three and a half decades of service.

Yet it is even more so for Hubble, a telescope that was once seen as little more than an audacious fantasy, that came close to cancellation, and was so flawed upon its arrival in orbit that it was almost abandoned.

Fortunately for us, Hubble survived all that. And despite the launch of the new James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble’s gaze is still very much in demand. Last year its operators received requests for six times more observations than the telescope had time to carry out. Those that were lucky enough to win time seem to have put it to good use: in 2024 more than a thousand research papers were published on the data it sent back. No other space telescope, Mars rover, or deep space probe has had anything like the lifespan or productivity of Hubble.

The idea of building and launching a giant space telescope was first seriously considered in 1946. It must have seemed like a fantastic idea, one as audacious as today’s dreams of building a telescope on the Moon or on the fringes of the solar system. In a paper of that year, Lyman Spitzer sketched out what such a telescope would be capable of doing. It could, he suggested, outpace any on Earth, settle the question of life on Mars, and change our basic concepts of space and time.

The challenge of building and operating such a thing, Spitzer acknowledged, would be tremendous. Yet the benefits would be enormous, and so over the following decades he, along with other motivated astronomers, pushed NASA to build a large space telescope.

Even as the technological obstacles faded, however, the idea faced resistance. Other astronomers feared the high cost of the observatory would smother smaller projects. Neither was Congress a fan. Funding for the project, along with much of the rest of America’s once-bright future in space, was cut in the mid-1970s.

Thankfully, with the support of the European Space Agency and renewed funding for NASA from 1977, work on the telescope went ahead. By the early 1980s construction was done and the observatory was given the name Hubble in honour of the great twentieth-century astronomer. But then, sadly, Challenger exploded, the space shuttle was grounded, and getting Hubble into orbit proved impossible before the end of the decade.

Finally, however, on April 25, 1990, the Space Shuttle Discovery lifted off with Hubble stowed in its cargo bay. After reaching a record altitude - engineers wanted Hubble placed as high as possible to maximise its lifespan - Discovery’s robotic arm lifted the telescope out of the cargo bay and set it flying free in space.

By then, as the New York Times ruefully noted, the question of life on Mars had been answered. But hopes were still high for the telescope. Nothing like it had ever reached orbit before, and NASA, still reeling from the shock of Challenger, was hoping the mission would give the agency a much-needed boost.

Yet things did not go well. After Discovery departed, engineers grappled with a series of problems affecting Hubble. Its communications and control systems did not work as well as hoped, and operators struggled to point it accurately at its targets. But then, after it captured its first images, an even worse problem emerged. Incredibly, the primary mirror was flawed. Hubble, it turned out, was incapable of taking the crystal-clear pictures astronomers had promised the world.

For NASA, the failure was a huge embarrassment. Comedians lampooned the telescope. In one movie, Hubble was even listed among the great engineering disasters of the twentieth century, placed between the Hindenburg and the Titanic.

Some wondered if NASA would simply abandon the telescope, or bring it back to Earth for repairs. Instead, they decided to fix it in orbit. During a mission at the end of 1993, the Space Shuttle approached Hubble, grabbed it with a robotic arm, and held it in place while astronauts installed corrective optics.

In January of 1994, the astronomical world waited with bated breath as NASA tested the new setup. Fortunately it worked. The telescope’s performance was, the engineer leading the repair said, “as perfect as engineering can achieve and the laws of physics will allow".

Soon Hubble was hard at work. In 1994, the telescope delivered the first convincing evidence that black holes really existed, sent back images of planet-forming disks around young stars, and watched, in July of that year, as a comet smashed into Jupiter.

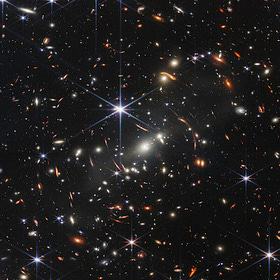

Over the three decades since, Hubble has remained at the forefront of astronomical research. Its position, high above the Earth’s atmosphere, allows it to see stars and galaxies more clearly than we can from the surface. It has picked out individual stars in the Andromeda Galaxy and seen galaxy clusters far older and more distant than any other telescope, bar the James Webb, ever has. And it has, as Lyman Spitzer foresaw, reshaped our understanding of time and space.

Indeed, it was observations from Hubble that, in 1998, helped astronomers discover the strange effects of dark energy. Only Hubble was capable of measuring the supernovae in distant galaxies that allowed researchers to trace the expansion of the universe. And it was those results that revealed the expansion was accelerating rather than slowing as had been expected. Today dark energy seems to be fundamental to modern cosmology, even if we still do not really understand what it is.

Yet, despite its cosmic visions, Hubble is still very much bound to our mortal world. Every year the tenuous outer atmosphere drags it a few kilometres lower, and so a little closer to burning up in the thicker lower atmosphere. Neither is it immune to the ravages of time and the harshness of space. Hubble was last serviced by astronauts in 2009. It has, since then, suffered a number of failures and fallen several times into a safe mode.

Its operators hope Hubble will survive until the 2030s. But without another visit from astronauts its time is limited. Jared Isaacman, the proposed next administrator of NASA, has in the past suggested sending someone to fix it up. Without the Space Shuttle any such mission would be hard and dangerous. But if it happens, and it might, then the world’s greatest observatory could one day find itself celebrating half a century in orbit.

Read More

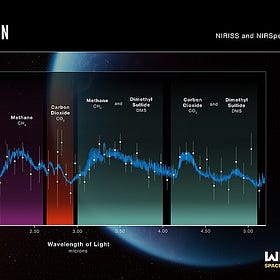

The James Webb Still Hasn’t Found Life on K2-18b

A year ago, rumours surfaced of an impending discovery of alien life. They focused on the planet K2-18b, an intriguing wor…

Things Are Bigger Than We Imagine: On the Hidden Threads of Creation

There was a time, long ago, when we were conceited enough to believe the Earth and humanity lay at the centre of creation. Kings and emperors proclaimed themselves the rulers of the universe, and thought they alone somehow held sway over the stars and planets.

I'm old enough that, in grade school, I remember how they gathered the whole school in the auditorium to watch Mercury launches on TV, so I've lived through the saga of the Hubble. I remember the shock and disappointment of its defective optics and the joy of the repairs. It has, indeed, been a long and great career. Fixing it and boosting it to a higher orbit would make for an amazing space mission.