Project Mercury and the SOFAR Bomb

Why bombs were hidden on the first space capsules

Project Mercury was supposed to be fast, and it was supposed to be simple. After all, Sputnik had made it starkly clear the Soviets were ahead, and America feared falling even further behind. The newly created NASA quickly struck back with Explorer 1, launched less than four months after Sputnik, but by then the Soviets had put a dog in space and everyone knew a human would be next. To have any hope of getting there first, Mercury had to be as fast and as simple as possible.

Except, of course, that putting a man into space for the first time was anything but simple. First you needed a rocket, and the ones America had in 1959 still had a nasty habit of blowing up. Then you needed a capsule – and this was supposed to be dumb, just something a person could sit in for a few hours and sail safely through the vacuum of space. And then you needed to bring him back to Earth.

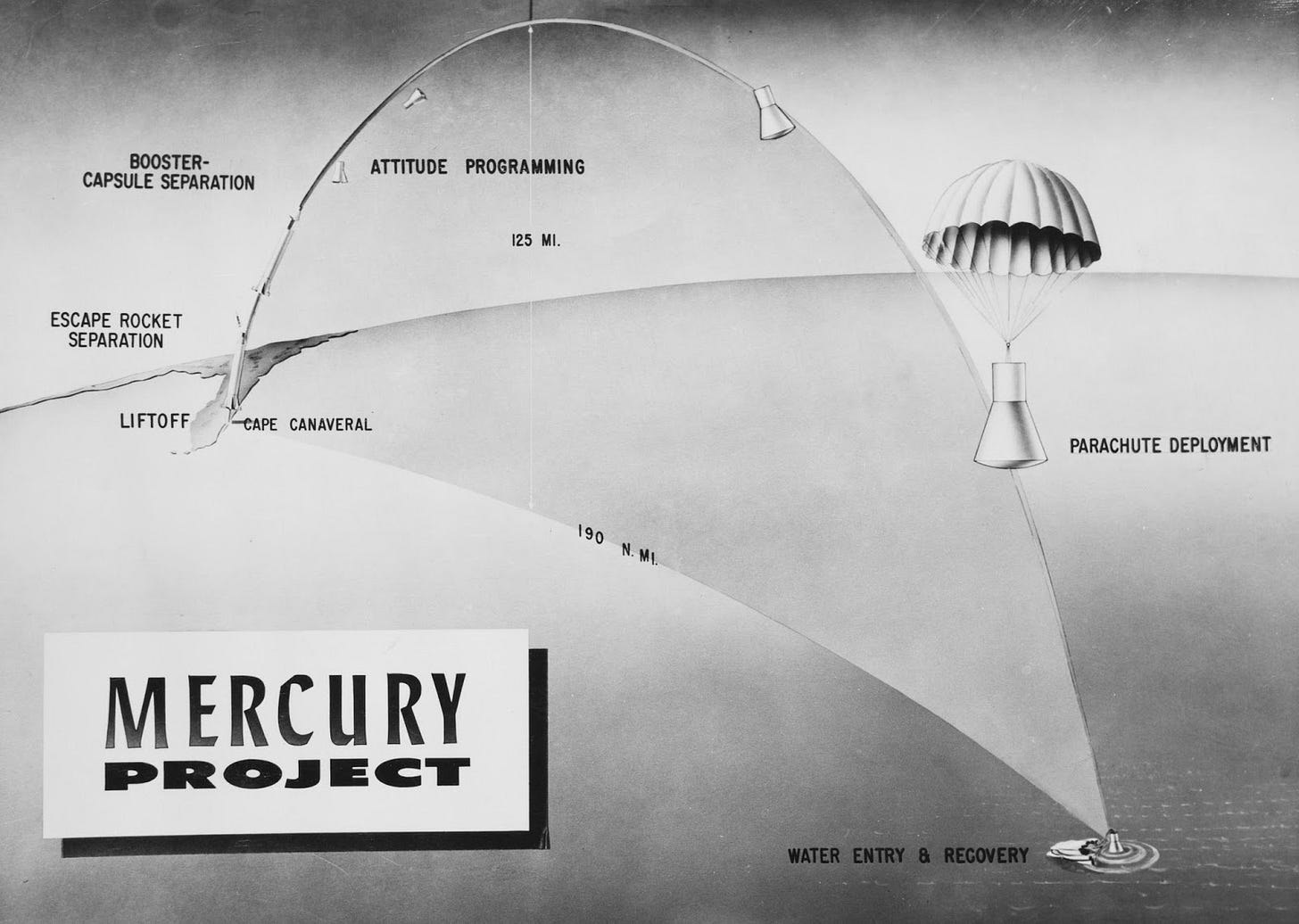

For this last bit, America chose to use the oceans. To return to Earth, an orbiting capsule first needs to fire its thrusters, a burn that slows the capsule and drains it of the energy needed to remain in orbit. After that it will fall, and if you time the burn correctly, it will descend towards a chosen spot on the ground. Put that spot in the ocean, and things are simpler: water is more forgiving than solid rock, at least when it comes to things falling at high speed.

But afterwards things can be complicated. A capsule must float; it must be able to survive waves and whatever else the weather throws at it; and it must be able to be found. And none of that is especially easy. In Project Mercury one of the capsules sank, a disaster which almost took an astronaut with it, and two others came down hundreds of miles off course, each invoking a search over vast stretches of the ocean.

This was a time before the navigation systems we rely on today. There was no constellation of GPS satellites, and no network of relay satellites to transmit distress calls. The deep ocean was vast, mysterious, and largely out of reach. If a capsule came down five hundred miles short of its target, as one of the first test flights did, then finding it was akin to looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

What was needed was a way to locate capsules amidst the waves. At first, uncertain of what would work, NASA threw almost everything they could at the problem. An armada of ships and aircraft were scattered across the ocean before every flight, and the capsules themselves were fitted with an array of aids to assist in finding them. They scattered chaff as the parachutes opened, hoping it would appear on radar, triggered radio beacons on splashdown, and dropped bombs that would explode deep under the waves.

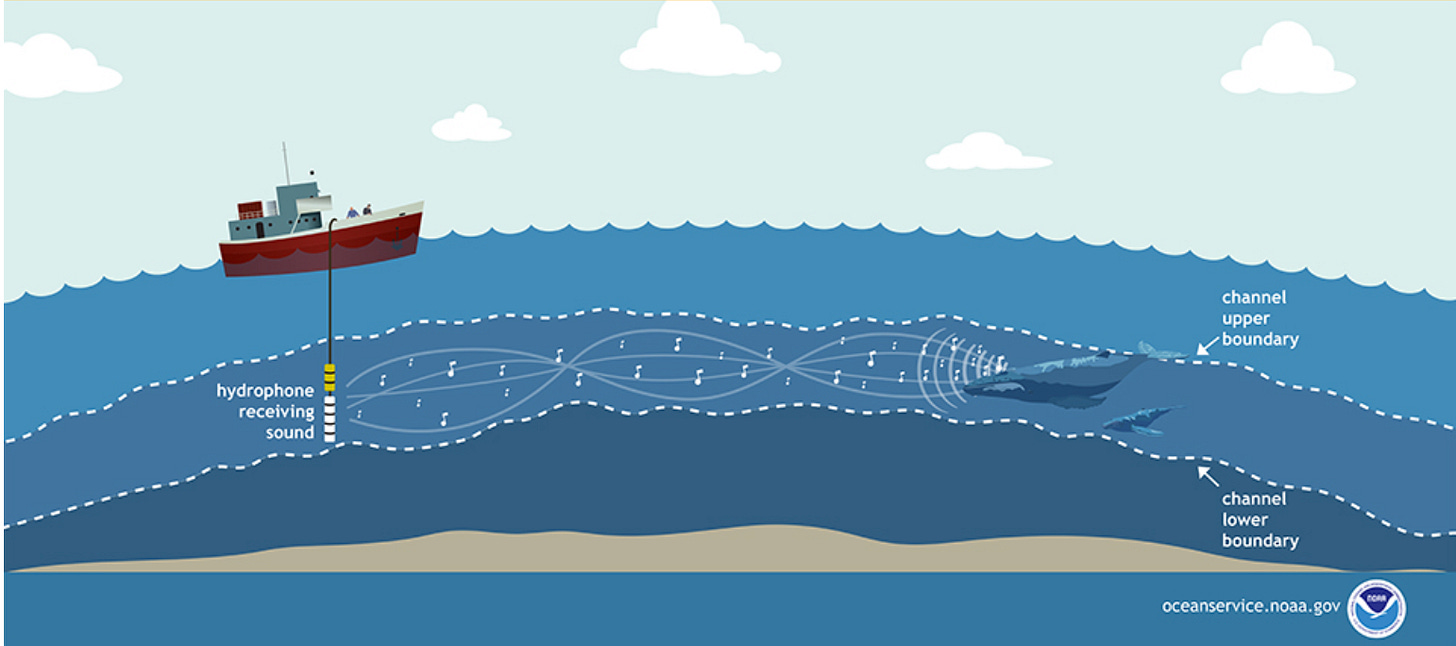

This last idea, that of the SOFAR bomb, relies on an oddity of the deep oceans. There, roughly a kilometre below the surface, lies a sound channel. If a bomb can be detonated in this channel, the sound of it can be picked up thousands of miles away, and that offers a way to hone in on the position of whatever has dropped it.

The reasons why this works are subtle. First, of course, is the simple fact that sound travels more easily through water than through air. That makes logical sense: sound moves through the vibrations of particles, and those particles are more closely packed in water than in air. This also means sound travels faster through water than it does through air: the speed of sound in fresh water at room temperature, for example, is four times that in air.

The speed of sound in water, however, also depends on both pressure and temperature. In colder water sound travels more slowly. The deeper under the surface of the ocean you go the colder things normally get, and so if all else is equal, sound waves moving deep under the waves should travel more slowly than those near the surface.

But, as always, things are not equal. The deeper into the ocean you go, the more water you have pushing down on you, and the higher the pressure you experience. As pressure increases, sound travels faster. Initially, as you descend under the waves, the change in temperature dominates and sound slows down. But at some point, approximately a thousand meters deep, pressure begins to assert itself, and sound speeds up again.

This creates a minimum, a distinct depth at which sound waves reach their slowest speed. If a sound originates here, it will stay here. If it rises, it will be reflected down. If it falls, it will be pushed back up. The only way it can move is within the layer itself, horizontally under the waves.

This implies two things. First, that sound waves cannot enter this layer. Only what is made within it can be heard by someone else listening inside it. And second, that sound waves cannot leave: any noise originating within this layer can thus be heard at enormous distances. Whale song is a good example of this: it can travel across an ocean, and allow a creature off the coast of Ireland to communicate with another swimming near Virginia.

We have developed two easy ways to create sounds underwater. One is to drop a hollow metallic sphere. At the right depth and pressure it will be crushed and the sound of the implosion will echo through the underwater channel. The other – the method used on Mercury – is to drop a bomb, use a pressure sensor to trigger a detonation, and then wait for the sound wave to travel through the water.

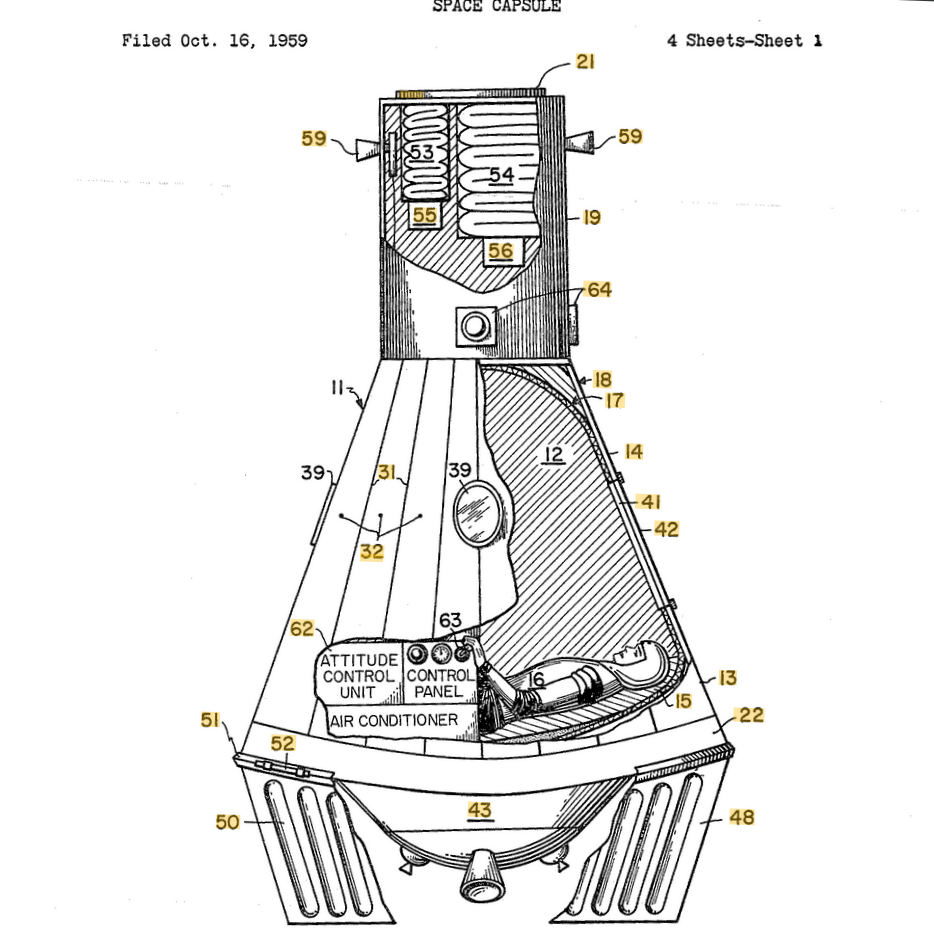

Each of the early Mercury capsules carried two such SOFAR – SOund Fixing And Ranging – bombs on board. One was stowed with the parachutes, and would be thrown out as they deployed. It would fall in the ocean and give any waiting ships a bearing upon which to look for the spacecraft.

The other was stowed within the capsule itself, and would only detonate if the whole thing sank. This would send a second location pulse to ships. But the explosion was also intended to destroy vital components inside the capsule, and thus prevent the Soviets from ever retrieving American designs.

Both bombs had a range of about three thousand miles. Hydrophones installed as part of Cold War efforts to track submarines could listen for them, as could vessels equipped with listening equipment and special buoys dropped by aircraft. All that gave the Navy plenty of points with which to triangulate the signal.

On September 9, 1959, all this was put into practice. Big Joe I, an uncrewed test capsule, was launched from Cape Canaveral. Things did not go to plan. A few minutes into the flight, the booster failed to jettison. That made everything heavier than it should have been, and to compensate the engines burned longer. Yet it wasn’t enough. When they ran out of fuel, the spacecraft was still coming in too steep. It landed five hundred miles short of its target.

But everything worked: the chaff deployed, an automatic radio beacon was picked up by a nearby aircraft, and the bomb exploded deep under the water. It took less than two hours to confirm the capsule’s location via the SOFAR channel, and the recovery operation itself was done within eight.

Overall, however, SOFAR proved less useful than hoped. The Navy often took hours to process the data from its microphones, and even then the results would reflect the point at which the parachutes had opened rather than the actual location of the capsule. When Mercury-Atlas 7 splashed down two hundred miles off-target, it was the radio beacons that first alerted search crews, not the bomb.

These difficulties, along with the effectiveness of radio beacons and water dyes, spelled the eventual end of the SOFAR bomb. After the fourth manned flight, NASA decided to drop both the bombs and the chaff. They were not used again on Mercury, nor on Gemini or Apollo. The Shuttle, of course, had no need for them, and by the time American capsules started splashing down in the oceans again, global positioning satellites had rendered all other techniques unnecessary.

Yet the bomb is a testament to a time when spaceflight was new and engineers were unafraid to think creatively. Project Mercury had to be fast, and there was no time to run years of analysis to prove what would work or what wouldn’t. Engineers were pragmatic, they tried new things, and if they proved unnecessary they weren’t afraid to move on.

True, not everything went right. There were near misses, close calls, and moments that could easily have ended in tragedy. But Mercury did succeed in putting a man into space, even if the Soviets were first by a month. And for a brief time, the sounds of those bold missions echoed through the depths of the oceans, accompanied by the songs of the whales and the mechanical whirr of the submarines.

Read More

Notes On Learning Hard Things

The number one most read page on my site is a guide to learning physics.

The Biggest Solar Flare of 2025

The Quantum Cat is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Hasselblad Cameras of Project Mercury

Unless otherwise specified, all images in this article are thanks to NASA and especially to the March to the Moon archive of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo photography.The Quantum Cat is a reader-suppor…

In a spherical wave guide, near the signal, the strength of the signal drops off as the inverse of distance. At the "equator" of the impulse, the signal doesn't diminish, and further away it can actually increase. At the antipode, it can be quite strong again -- but chaotic, since the many converging impulses are not necessarily in phase after the long journey half way around the world.

There are some interesting examples of earthquake waves also experiencing antipodal amplification.

It is worth remembering that the original NASA plan for an Earth satellite was Vanguard, which was a radio beeper in a gold-plated spherical shell (I think around 30 cm diameter). It was to be launched on a custom designed rocket that was supposed to be a technological wonder. When Sputnik I went up, Vanguard wasn't ready, and Plan B was the Explorer satellite on a US Army Jupiter-C ICBM. Months later, NASA embarrassed themselves by publicly broadcasting a series of attempted Vanguard launches, each one exploding immediately upon lift-off. A consultant figured out that the NASA engineers had only analyzed the vibrational modes of the rocket with one end on the launch pad. As soon as the rocket lifted off, the vibrational pattern changed significantly and the rocket's flimsy—er, optimized—structure failed. With reinforced structure, one Vanguard rocket finally got its shiny little payload into orbit.