The Hasselblad Cameras of Project Mercury

On the beginning of NASA's long relationship with Hasselblad cameras

Unless otherwise specified, all images in this article are thanks to NASA and especially to the March to the Moon archive of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo photography.

Deke Slayton was supposed to command Mercury-Atlas 7. But medical tests had found a minor heart problem - idiopathic atrial fibrillation - and sparked a furious row over whether he could do the job or not. NASA chose to play it safe. Even if Slayton was fit enough to come back alive, no one could deny that Scott Carpenter - who had no known heart problems - was the less risky option.

And so Carpenter became the sixth man to fly in space. He enjoyed himself. As he flew three times around the world in his capsule, the Aurora 7, he watched the sun rise and set with delight, tried to spot Florida out the window, and released a multicoloured balloon from the back of the spaceship.

Only on his third and final orbit did he realise he was running low on fuel and that the time for re-entry was fast approaching. Too late he fired the retro-rockets, and aimed twenty-five degrees off-target. His fuel tank was empty, and he had no chance to correct the errors.

In mission control they feared disaster. But fortunately the capsule made it down, even if Carpenter overshot the desired spot by two hundred and fifty miles. It took almost an hour to find the Aurora 7, time enough for television presenters to start raising the terrible prospect that America had lost an astronaut on re-entry.

No matter. Carpenter was alive and in one piece. When the rescuers arrived, he was found happily floating on a raft next to his listing capsule. A somewhat chaotic recovery operation followed, and then Carpenter was hoisted into a helicopter, and back on solid land before the day was out.

Happy, and lucky maybe, but NASA was less than pleased. Carpenter would never fly again.

Wally Schirra was to command the next flight, and he was determined to do better. Carpenter, after reaching orbit, had struggled to load his camera with the special film needed to photograph the limb of our planet. He had fallen behind the flight plan at that point, and then compounded the fuel concerns by rolling the capsule to take photos and conduct experiments.

What was needed, Schirra realised, was a better camera. He asked around for advice, and soon settled on the commercially available Hasselblad 500c. It had to be modified for use in space, of course: astronauts wore heavy gloves and helmets, and the Swedish Hasselblad had not been designed with this in mind.

To adapt it, engineers removed the reflex mirror and replaced it with a straight viewfinder that an astronaut could hold to the glass of his helmet. The camera itself was painted matt black to reduce reflections in the window of the spaceship, and every unnecessary element was removed to eliminate as much weight as possible.

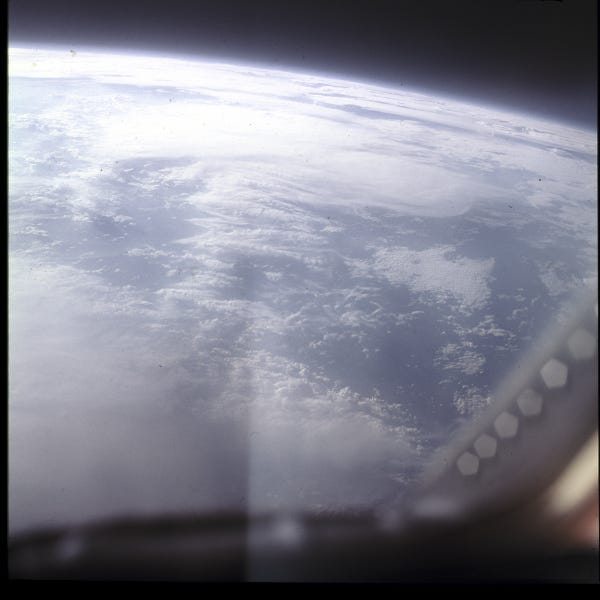

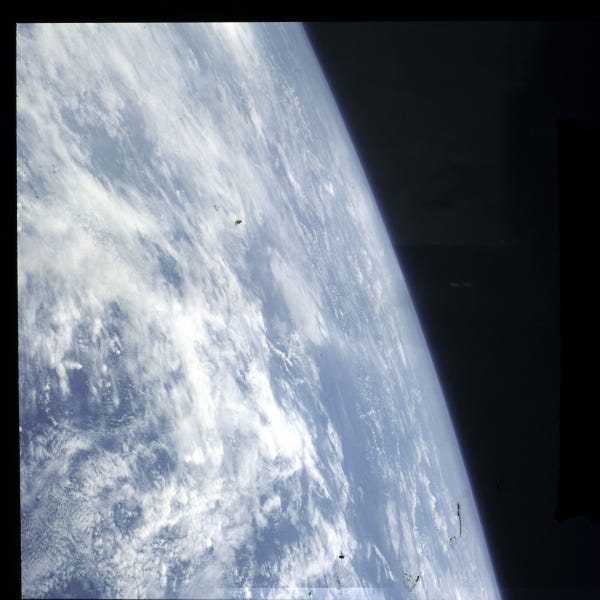

Schirra carried this modified Hasselblad on Mercury-Atlas 8, in the capsule he named Sigma-7. But the photographs he took with it were poor - the Earth’s clouds turned out to be much brighter than had been anticipated, and his pictures mostly came out overexposed.

Despite that, NASA recognised the promise of these cameras, and sought ways to increase the data they could return. Key to this was efficiency. Cameras in those days relied on rolls of film to record their images. But mass was precious, and since every ounce taken onboard had to be accounted for, astronauts could not carry that many rolls of film with them.

This sharply limited the data Schirra’s cameras could capture. A NASA report put it simply - “the amount of information that can be recorded is determined by the ultimate performance of the film rather than by the lens”. To do better, NASA didn’t need another camera, they needed to improve the efficiency of the film they used.

With the help of the Hasselblad company, NASA started this effort by increasing the capacity of the camera. The commercial model was designed to capture twelve exposures before the film had to be switched. But the modifications boosted this to seventy, reducing the need to change films manually.

Alongside this, NASA changed from using 35mm film to using 70mm, a move that increased the resolution of the images captured. And they investigated ways to make the film itself thinner and thus lighter, an effort that eventually allowed the camera to capture two hundred exposures per roll of film1.

For the ninth and final of the Mercury flights, however, it seems astronaut Gordon Cooper carried pretty much the same camera design as Schirra did. Probably not the exact same one - two separate Mercury Hasselblads have turned up in recent years - though one modified in more or less the same way for use in space.

The ninth Mercury flight was to be the longest. Carpenter had gone around the world only three times. Schirra had made it six. Gordon Cooper, in that final flight, would aim to spend a whole day in space, an effort that would require circling the Earth almost two dozen times.

That extra time gave Cooper plenty of opportunity for photography. He marvelled at the detail he could see from his window - on the high plateau of Tibet, he said, he could see villages and roads, and even pick out streams of smoke blowing from chimneys. This, he tried to capture in some of his images.

Yet his photography was not all for pleasure. Engineers from MIT asked for images that would aid them in building a navigation system for Apollo. Meteorologists wanted infrared images, and others requested observations of the Moon setting over the horizon of the Earth. Everyone, it seemed, was starting to see the potential of photography from orbit.

“Man, all I do is take pictures, pictures, pictures!”, he complained, drifting within range of Florida.

In his final two laps around the Earth, things started to go wrong. Error lights lit up his dashboard. One warned of a slow deceleration, something Cooper should have experienced as a slight return of gravity. As he felt no such thing, he concluded it was likely a false alarm.

But then all attitude readings were lost. A short-circuit left the automatic stabilisation system without power, and the upcoming re-entry would have to be done manually. Even worse, carbon dioxide began to build up inside his suit, a sign that the electrical problems were affecting the oxygen supply.

“Things”, Cooper said then, were “beginning to stack up a little”. But the man was more than equal to the task. He kept his pitch, thirty-four degrees, fired the retro-rockets at the precise moment, and splashed down just four miles from the waiting ship.

And that was it. Project Mercury - despite some efforts to promote a tenth test flight - came to an end. NASA moved on to Gemini, to practising spacewalks and dockings, and then on to the Moon itself. The lessons of Mercury - and, indeed, its cameras - proved invaluable in everything that was to come.

This two-hundred exposure film was not achieved in Mercury, but only towards the end of Gemini and the start of Apollo.

Read More

The Myth and Mystery of The Tunguska Impact

Suddenly... the sky was split in two and high above the forest the w…

On Progress and Revolution in Physics

Speaking generally, we might say science progresses in two distinct ways.

It’s nice to learn of The March to the Moon photographic archive. Thanks for sharing the link.