The Debris of Creation: Hubble Watches Worlds Collide

On the discovery of violent collisions around Fomalhaut

As always, welcome and thank you for reading! For those who are new here, this is a newsletter on space and physics. This week, paid subscribers will get an additional post on the physics of Aristotle. For full access to this and to our full archive, you can become a paying subscriber here.

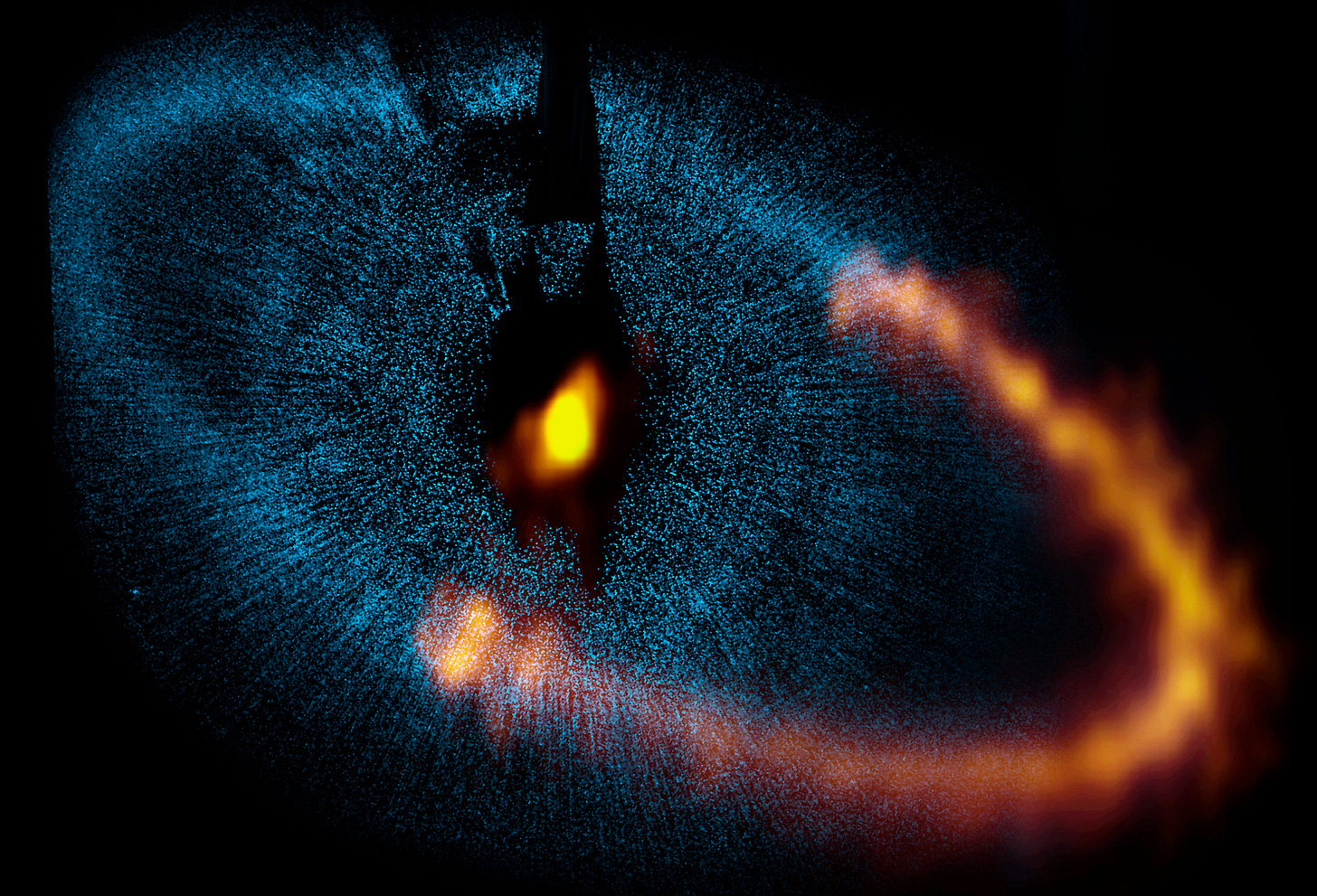

The spectacular cloud of dust and debris around Fomalhaut has long been a favourite target of astronomers. After all, the star is one of the brightest and closest of the southern sky, and its debris cloud makes for good photos. Those taken by the James Webb Space Telescope capture glowing rings looping around the star; those from Hubble show a bright outer ring encircling inner debris fields as if to create a cosmic all-seeing Eye of Sauron.

Since the star is around half a billion years old – young, as these things go – this cloud is thought to be a disk of rock and dust slowly coalescing into planets. Its inner rings, imaged by the James Webb, might already be shaped by the passage of large planets sweeping around the star. The outer ones, seen by Hubble, are probably home to countless dwarf worlds known to astronomers as planetesimals.

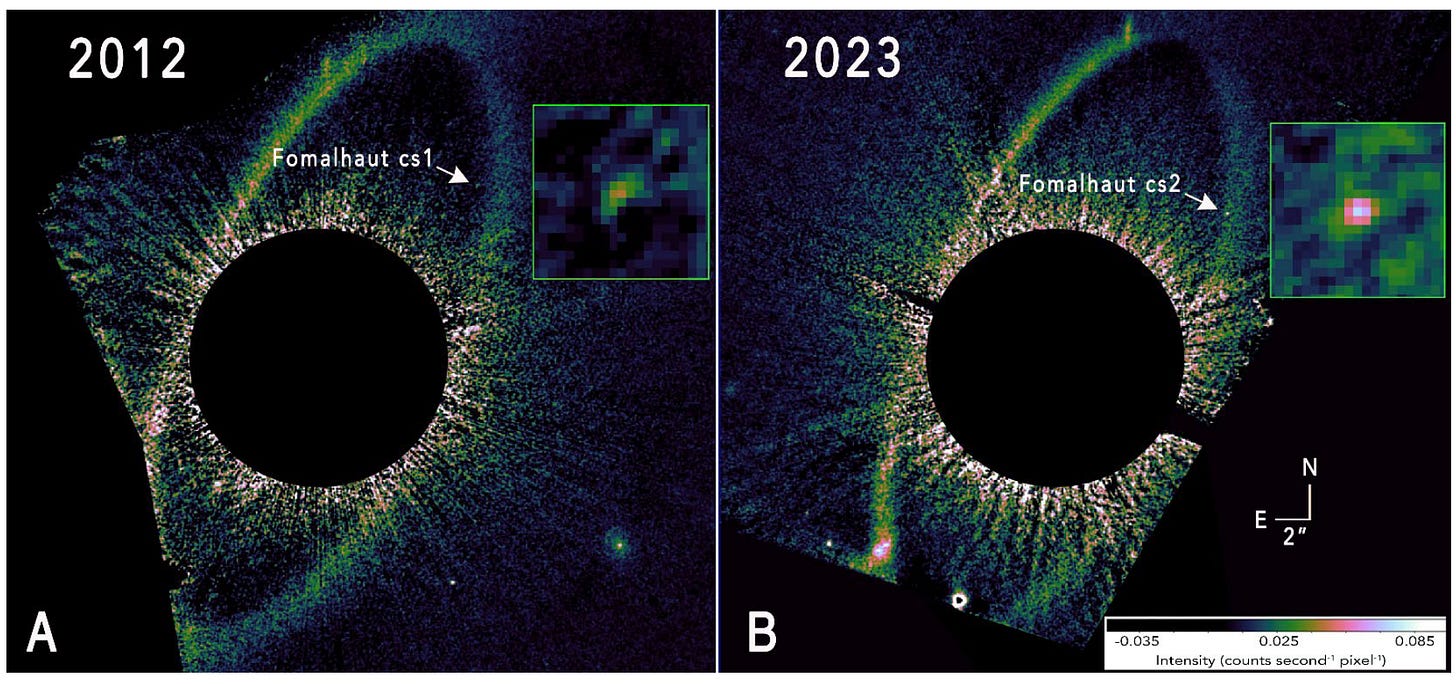

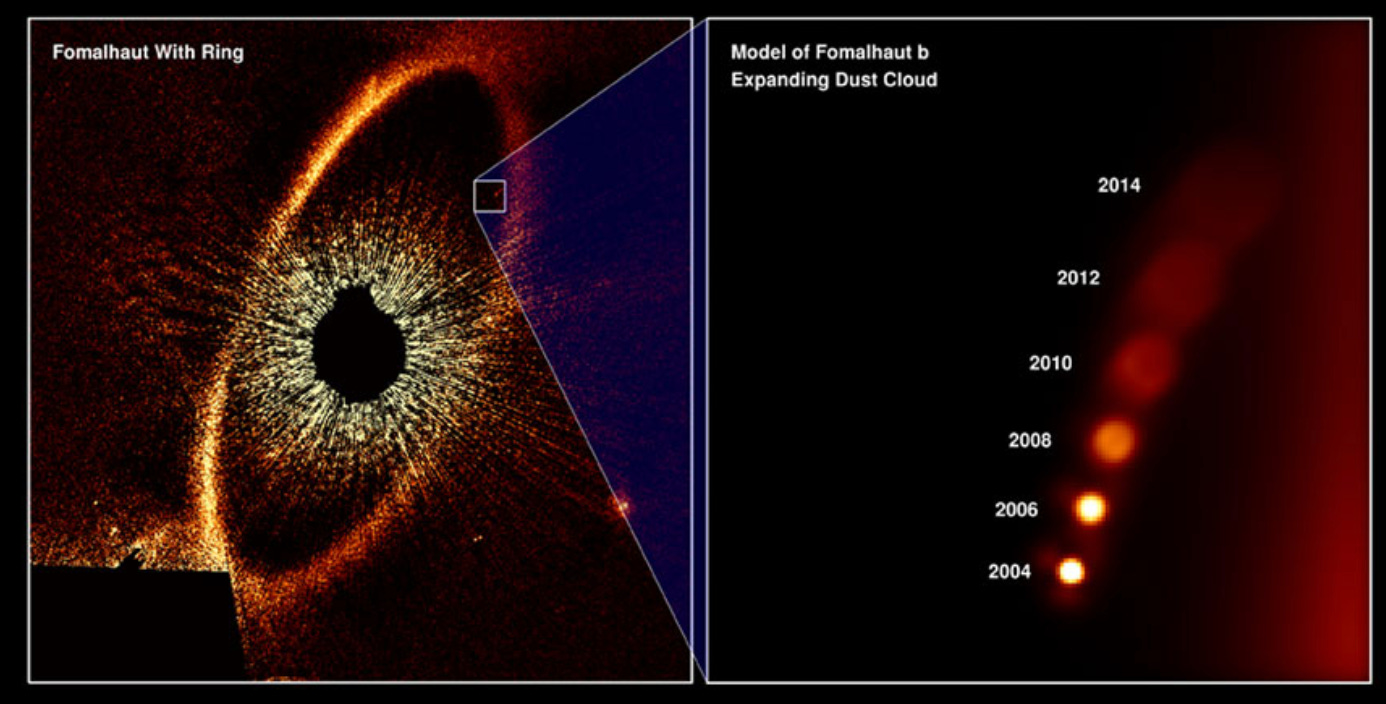

In 2004, headlines were made when Hubble spotted something that looked like a planet in those outer rings. The discovery was hailed as a big success: indeed, it marked one of the first times we thought we had taken direct images of a world around another star. But things soon got weird. In optical wavelengths the object was far brighter than any planet should be, yet when telescopes examined it in infrared wavelengths they failed to spot anything at all.

How to explain this? Some astronomers clung to the idea it was a planet. But to salvage the big discovery, they had to wrap it in a thick cloud of dust. If this layer existed, they argued, it would reflect starlight and make the world look far brighter than it otherwise would. Others pointed out that the planet itself was unnecessary. Instead, they said, we may simply be seeing a cloud of debris formed by a violent collision between worlds.

In the decades since, the evidence has mostly favoured the second idea. When Hubble revisited Fomalhaut in the early 2010s, it found the object expanding and fading in size, just as a debris cloud might be expected to. Even more convincingly, it seemed to be moving radially away from the star. That would make sense if grains of dust were being blown outwards under the radiation pressure of the star, again as might be expected after a collision.

By 2014, the object had vanished altogether, and it has remained elusive ever since. In 2023 astronomers led by Paul Kalas of the University of California searched for it again. Once again they used Hubble, but, as they outlined in a recent paper, they still couldn’t find any clear sign of the dust cloud. Yet as they searched, they did find something else: a new point-like object had appeared around Fomalhaut.

When Worlds Collide

The idea that small planets might be smashing into each other is not particularly surprising. Fomalhaut is a young star surrounded by a large and chaotic cloud of debris left over from its formation. Within it, chunks of rock and ice are moving, accumulating mass, and trying to sweep their orbits clear. This is how star systems form, and eventually it may well settle down to become a calm and respectable system like our own.

But right now, things look far from ordered. Orbits are still in conflict, and sometimes big things crash into each other. On most occasions these are minor events, part of the natural gathering of matter. But at other times they are cataclysmic: two small worlds smash into each other at speed, the violence of the collision shatters them, and a great cloud of dust and rocky fragments takes their place.

This probably describes both events that we have now seen. Surprisingly, however, the objects are unlikely to be large. We are not watching planets like Venus crash into Mars, according to Kalas and his team, but instead seeing collisions between large asteroids or prototype worlds.

The logic behind this is simple: big planets must be few in number, and collisions between them must be rare. It is unlikely we would have witnessed two such events in the past few decades. Instead, it is more reasonable to say we are seeing collisions between dwarf planets or large asteroids. These objects should number in their millions, and a big impact could come roughly once every few dozen years.

But the authors also see hints that more is happening than we currently know. The new object appeared close to the site of the previous one, which seems like an odd coincidence. It is possible, Kalas says, that rings of debris happen to cross at this point, though the observations we have so far seem to contradict this idea. Another option, he writes, is for an unseen planet to be herding smaller worlds into this particular region.

These debris rings may also be shaped by the two small stars that orbit Fomalhaut. Both are quite distant, and will not normally disturb the system. Yet at times they do sweep inwards, and their gravitational pull is bound to have some effect. Indeed, the stars may sometimes direct small planets onto collision courses, and thus help instigate bouts of chaos.

Under Heavy Bombardment

We do not have to look far to find evidence of similar events elsewhere. Craters on our own Moon tell of a cataclysmic period long ago when the Earth and its satellite were bombarded by asteroids and comets. Where these came from is still uncertain, but several theories pin the blame on the outer edges of the solar system.

In one model, the gas giants – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune – fell into a gravitational resonance. Saturn may have been flung outwards; indeed, some simulations suggest it was born closer to the Sun than Jupiter was, and that the planets swapped place in a moment of violence. The outward swing of Saturn unsettled Uranus and Neptune, and might even have sent a fifth gas giant careening outwards.

If so, that extra planet has long been lost, and now floats alone in the galaxy. But its movements, or those of the other gas giants, pushed the cloud of ice and rock at the edge of the solar system into chaos. Collisions would have been frequent, and a rain of asteroids would have fallen on the inner planets.

Today, of course, things are much calmer. The planets follow regular, well-swept orbits. The asteroids have mostly been herded into groups, and collisions between things are now rare. But this might not last forever. Models show our solar system is still a chaotic system. A small disturbance – perhaps the approach of another star, perhaps the wandering of a stray comet – could throw things off balance.

If that happens, simulations cannot accurately predict the outcome. Models show different catastrophic possibilities: a planet could plunge into the Sun, Mercury could smash into Venus, or Mars could be hurled out into interstellar space. Fortunately, all these scenarios take tens of millions of years to play out, and so we’d get plenty of warning of the impending chaos. And with that, hopefully, we would have time to do something about it.

Read More

Project Mercury and the SOFAR Bomb

The Quantum Cat is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Notes On Learning Hard Things

The number one most read page on my site is a guide to learning physics.

How Dust on the Ocean Floor Hints at a Recent Near-Earth Supernova

However big you imagine a supernova to be, the reality is certainly bigger. To put it one way, an exploding star can briefly outshine the combined light of every other star in a galaxy; to put it another, a supernova at the distance of Pluto would hit you with more energy than a hydrogen bomb exploding just outside your front door.