The Mysterious Origins of the Third Interstellar Comet

The latest interstellar comet probably isn't an alien spaceship. But that doesn't mean we know where it really came from.

Three weeks ago, a robotic telescope in Chile spotted a comet moving somewhere close to the orbit of Jupiter. That’s not unusual. Telescopes pick up comets with some regularity, and since many are faint and travelling inwards from the frozen outer solar system, we often catch them only as they traverse the space between Neptune and Mars.

Afterwards, the usual apparatus of comet discovery swung into action. A dozen or so telescopes turned to track it in the early days of July; and as they did, astronomers across the world revisited older images captured throughout the months of May and June. It turned out we’d seen it before, or at least our telescopes had, and so we were able to retrace its movements over the span of a few weeks.

And that is when things started to get interesting. As astronomers pinned down the comet’s orbit, they found it was moving too fast to have originated in our solar system. Instead it is falling inwards from interstellar space, coming at us from the direction of the constellation Sagittarius. Before the end of the year it will pass within the orbit of Mars, swing past that planet at speed and possibly with style, and then head back out towards the stars.

It is, then, the third interstellar comet discovered by humanity. Like the two before it - 1I/Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov – the comet is probably a lump of ice, made of some mix of water, carbon monoxide, nitrogen, dust, and maybe other things like ethane and methane. Early images show it surrounded by a fuzzy coma, probably forming as its ices begin to heat up under the warmth of the Sun.

But it is also moving much faster than either of the two previous interstellar comets. 3I/ATLAS, as it has been named, is hurtling towards the inner planets at over two hundred thousand kilometres per hour, more than twice the speed Oumuamua attained. This velocity is probably a sign the comet is old, astronomers say, and that it might be far older than either of the two seen before.

That makes the question of its origins an intriguing one. If 3I/ATLAS is really as old as it now seems, it might have come from an ancient star, and so have formed in an earlier era of galactic history. That would mean we are seeing a relic of the distant past, and now have a rare opportunity to study something born not only around another star, but at a time long before the solar system came into being.

I. The Alien Spaceship Theory

Before we go any further, however, let us turn first to the Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb. He famously argued that Oumuamua was not a comet after all, but instead a piece of alien technology. It could have been sent deliberately, he says, or it might be the discarded trash of a galactic empire. Either way, of course, there is no real proof of this. But as Professor Loeb points out, there is no real proof of any other theory either.

Oumuamua was, to be fair, a strange object. It appeared to be long and thin, and so was shaped unlike any other known comet or asteroid. Spectral observations struggled to work out what it was made of, and, most puzzlingly, it seemed to accelerate as it passed the Sun, as though some internal engine were at work.

Astronomers have ideas about what could have caused all these things. One popular theory posits it was a “dark comet” made of hydrogen-rich ice and born in a molecular cloud rather than around a star. As it approached the Sun the ice melted, forming an invisible “dark” tail of hydrogen gas. The pressure of that escaping gas would have given it a thrust, and accelerated it away from the Sun.

But Loeb argues against this theory. A hydrogen comet would not survive for long, he calculates, and so would never reach the solar system. But even if it did, he goes on, it wouldn’t melt fast enough to produce the thrust seen. And anyway, he wrote in a recent essay, the scepticism shown towards his theory was unfair, and characteristic of a science resistant to unconventional ideas.

Loeb thus wasted little time in thinking about whether the new comet might also be an alien spaceship. 3I/ATLAS is, he says, unusual in many ways. It is moving fast, coming from an unexpected direction, and follows a path that would be ideal for mapping out the planets in the solar system. It is even on a trajectory that will hide it from Earth’s view as it draws close to Mars. At that point, he speculates, the comet could make a sudden and unseen manoeuvre.

If it does, the “probe” could then drop by Earth, scan us, and undoubtedly reveal that intelligent beings have been watching us from a distance. That might be good or bad, Loeb says. If the aliens are benign, then we have little to fear, and should even welcome the visit. But if they are hostile, we are probably doomed. The comet could even be a weapon, and so maybe its sudden appearance is the ultimate omen of death and destruction.

To put it politely, this is all a bit far-fetched. There is nothing about 3I/ATLAS that yet points to it being any kind of alien technology. Loeb’s main point, I hope, is that we should not completely dismiss the possibility of finding such an object. The cosmos is certainly a lot stranger than we imagine, and the prospect of spotting alien intelligence should not be ruled out. But the arrival of 3I/ATLAS is probably not that moment.

II. A Relic of an Ancient Star?

So, if 3I/ATLAS is a natural object, where did it come from?

There are, broadly speaking, two main possibilities. Either the comet formed around another star and then escaped or was cast off; or it formed in interstellar space itself, perhaps coalescing in a molecular cloud somewhere.

Oumuamua plausibly belongs to the second category. Although the debate about its age and origins has raged for years, its youthful appearance and slow incoming speed mean it could have recently formed in a cloud and then happened to drift into our solar system. There are signs that another comet – Hyakutake – might have formed in the same way, though unlike Oumuamua it was then captured by the Sun and now follows a long orbit between the planets.

Borisov, the second interstellar comet, seems more likely to be a stellar outcast. Plotting its path backwards finds a handful of nearby stars it could have come from, the most likely of which is a red dwarf named Ross 573. Around a million years ago, Borisov passed very close to this star. We might speculate it was born there, only to be later thrown outwards towards our Sun.

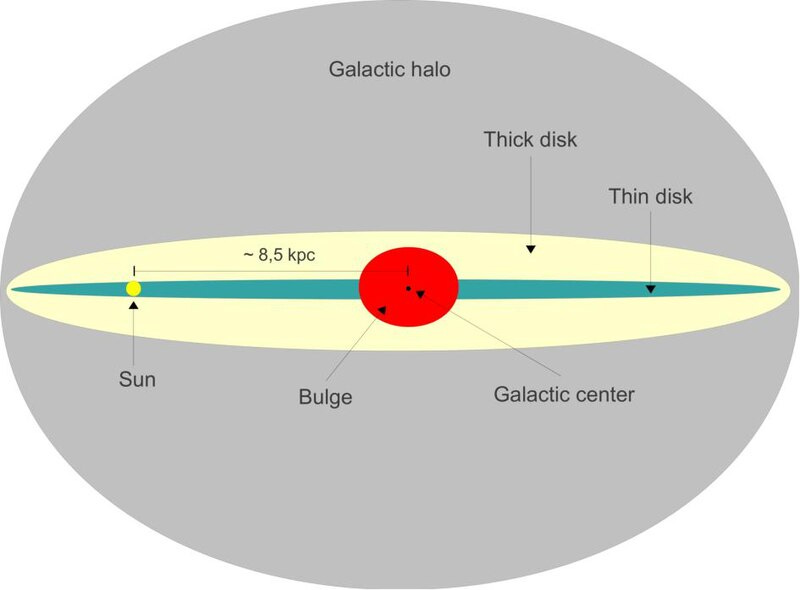

But 3I/ATLAS is travelling faster than either Oumuamua or Borisov. That means it probably didn’t come from some nearby star or cloud, but has instead spent untold years bouncing between the stars. In an early study of the comet, Matthew Hopkins of Oxford University argues it may come from the thick disk of the galaxy, that is, a layer of old stars that lies above and below the main plane of the Milky Way.

If so, we should expect 3I/ATLAS to have formed around an earlier generation of stars than the Sun. The comet itself may be at least seven billion years old, though how much of that time it has spent drifting alone in interstellar space is impossible to say. Based on this possible origin, Hopkins thinks we will find the comet to be rich in water, and that this should make it look different to normal comets as it approaches the Sun.

III. Next Time, Let’s Take a Closer Look

Comets like 3I/ATLAS and Oumuamua are fleeting visitors. They swoop inwards at high speed, fall rapidly towards the Sun and then fly outwards again, vanishing into the stars. The few months we get to examine 3I/ATLAS will be it, and by early next year it will be gone, fading into the distance never to return.

Yet these are fascinating objects. We ourselves have little chance to travel out to the stars. Even reaching the edge of the solar system can take half a century. Sending a probe to Proxima Centauri, the closest known star to the Sun, would take thousands of years at best. And certainly nothing is coming back – we will not be returning samples of the small planet known to orbit Proxima Centauri to study in the lab.

Interstellar comets, however, almost do that job for us. Instead of going out to the stars, we have pieces of them falling towards us. If we could send a spacecraft to visit 3I/ATLAS, we would have an opportunity to study something never seen before. We could even bring back a chunk of it, and so directly examine samples born around another star in our labs.

To do so, however, we’ll need to be prepared. Comets arrive with little warning, leaving no time to build and launch a probe from scratch. Instead, we could build one or more in advance, and then have them waiting at some convenient spot for the next interesting comet to arrive.

Indeed, the European Space Agency is already working on such a project. The Comet Interceptor mission is designed to wait at a spot a million miles from Earth. When a comet appears – and here they are more interested in the normal kind rather than the interstellar variety – the probe will head out, rendezvous, and collect samples of the comet’s tail.

The high speed of interstellar comets can make them harder to intercept, but that doesn’t make it impossible. And with the opening of the powerful Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, we’re likely to have an abundance of them to explore. Its cameras are expected to soon start discovering a few dozen of them every year.

So why not, then, plan a visit to one of these balls of ice and rock flung off by far distant stars?

Read More

What Dark Energy Means For The End of Time

Long ago, long before humankind had dreamed of science, of forces and atoms, of dark matters and dark energies filling the void, our deep ancestors looked up at the splendor of the night and wondered. How, some child must have asked, did it all begin? And then, after some thought: how will it all end?

The Future Is More Terrifying Than We Can Imagine

Half a century into its interstellar escape from Earth, the ship Blue Space stumbles across the mysterious ruins of…