The Myth and Mystery of The Tunguska Impact

What was it that exploded over Siberia in 1908?

Suddenly... the sky was split in two and high above the forest the whole northern part of the sky appeared to be covered with fire. At that moment I felt great heat as if my shirt had caught fire; this heat came from the north side. I wanted to pull off my shirt and throw it away, but at that moment there was a bang in the sky, and a mighty crash was heard... The crash was followed by noise like stones falling from the sky, or guns firing. The earth trembled, and when I lay on the ground I covered my head because I was afraid that stones might hit it.

~ S.B. Semedec

In time, the people of the Tunguska rivers came to believe it had been a god. An angry one at that: in his wrath the divine being had ripped the sky in half, sent a hot and terrible wind rushing through the forest, and left a million trees shattered and broken.

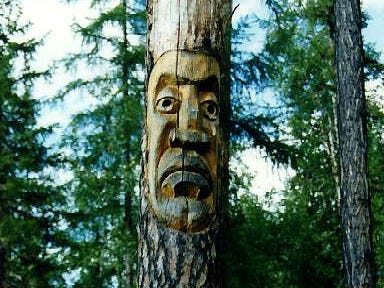

Out of fear of a lingering curse, few people dared venture into the afflicted lands. It became the terrain of Agdy, the Old Man, God of Fire and Thunder, and he was not a being who welcomed visitors. Reindeer were slaughtered to appease him, and it was said he would delay the spring thaws if anyone troubled him.

According to most accounts, the events took place early in the morning of June 30, 1908. A light appeared in the sky, travelling from the south-east to the north-west. It shone as bright as the sun and emitted a great heat. At some point it vanished in a flash of brilliant light and a roar of thunder, and in its place appeared towering pillars of smoke.

Observers forty miles away reported being knocked over by a hot and fierce wind. Tents were flung into the air and the people inside were bruised and knocked unconscious. It seems few people were killed – some reports mention two or three possible deaths – but an expanse of the Siberian taiga was destroyed, with trees blown down and burned over an area two thousand square kilometres in extent.

In the days afterwards, people across the world reported strange sights in the skies. Sunsets were unusually vivid and colourful across Europe and Asia. In London, newspapers noted that after the Sun had set the twilight faded slowly, and that by midnight people could still read in the streets without the need for artificial lighting.

All this, of course, was very strange. The people of the Tunguska rivers can be forgiven for thinking the events were divine in nature. They must have been something terrifying to witness – certainly, some of them seem to have believed the world was coming to an end. Indeed, the description they related bears a striking resemblance to some biblical descriptions of ancient catastrophe.

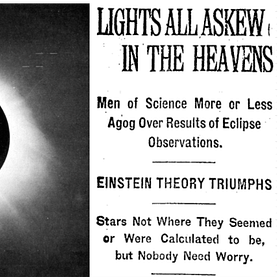

But others, including some in Siberia, sought a more scientific explanation. Shock waves picked up on seismographs around the world pointed to a single burst of energy released over Siberia. The colourful sunsets and extended twilights reminded some of those seen a few decades earlier after the violent eruption of Krakatoa.

Speculation thus focused on the fall of an asteroid, or the eruption of an unknown volcano. Yet the location was remote, and the world was on the verge of a tumultuous decade. Local newspapers left scattered reports in the days afterwards, but before long interest in the strange happenings of Siberia was overtaken by the pressing needs of politics, revolution, and war.

In 1921, as the situation in Russia slowly calmed, eyes once more turned towards Siberia. A geologist named Leonid Kulik had heard rumours of the events of 1908, and he persuaded the Soviet Academy of Sciences to fund an expedition. At the time no one knew exactly where the explosion had taken place, and so his first efforts focused on gathering reports and interviewing witnesses.

The results convinced him that something really had fallen from space, most probably an asteroid. He speculated about the presence of an impact crater lost somewhere in the Siberian wilderness, and wondered if a valuable supply of meteoritic iron might be found there. Yet few others believed him – the reports he gathered, he later wrote, were not considered sufficiently trustworthy.

By 1927, however, new evidence had emerged. Investigators reported rumours of a region of devastated forest, and an analysis of seismic waves reconfirmed the idea of an explosion over Siberia. The Academy thus funded a second expedition. Kulik once again ventured into the wilderness, and by all accounts had a terrible time: the trip had to take place in the narrow window between the thawing of the winter snows and the onset of the summer insects, and the impact site itself was remote and could be reached only by struggling through overgrown forest on foot.

Eventually, however, he found the region of devastation. It covered a “huge area”, he later wrote, of “radius about 30 kilometres”, extending to sixty kilometres in the surrounding hills. Within it, trees were blown down and its outer fringes were burned from above. At the centre was no crater, but instead a region of upstanding trees burned and “totally devoid of branches”, as though they had been swept by some powerful downblast.

In this and later expeditions, Kulik found no clear crater. Neither did he find a meteorite, nor any evidence of iron left from one. Instead he found signs of a flood in the valleys and in places pits or depressions in the soil. But none of this confirmed the idea of an asteroid impact. After all, if one really had hit the Earth in 1908, where had it gone afterwards?

Throughout recorded history, there have been reports of things falling from the skies. For a long time they were easy to treat with scepticism: in 1768, for example, the chemist Lavoisier investigated reports of a stone that fell from the heavens. Such a thing was improbable, he wrote, and the witnesses must have been mistaken and the stone simply struck by lightning.

Yet, if you look, similar reports are everywhere. Plutarch records one falling amidst a battle in 73 BC; Pliny the Elder tells of another falling in 466 BC. A stone preserved in Alsace fell in 1492, a rain of rocks took place over Normandy in 1803. Others killed farm animals in Brazil in 1836, in Ohio in 1860, and in Egypt in 1911. One even exploded over the Spanish capital of Madrid in 1896, killing no one but sparking panic among its citizens.

We now know asteroids hit the Earth with startling frequency. Most are small events, and most happen over the oceans or other remote and scarcely inhabited regions. A NASA database shows more than a thousand impact fireballs have been detected over the past forty years, suggesting that on average a decent sized strike happens somewhere on Earth once every two weeks.

The majority explode high in the atmosphere, and cause little damage on the ground. But a large one can penetrate further, and when it explodes it can be hard to ignore. The Chelyabinsk meteor of 2013 made headlines after it blew up over a Russian town. It was probably the most powerful of the last half century, and when it ripped apart and detonated at an altitude of twenty-three kilometres it released the equivalent of almost half a megaton of TNT.

That’s a lot, equal to a decent sized atomic bomb. Indeed, in the past thirty years, detectors have picked up six atmospheric fireballs with greater energy than the Hiroshima bomb of 1945. All, fortunately, took place at high altitude. But if a larger meteor than Chelyabinsk were to strike, and were to explode lower in the atmosphere – at a height of say five kilometres or so – the effect on the ground would be similar to that of a nuclear blast.

That hints at what might have happened in Tunguska. It was probably the largest object to strike the Earth in recorded history. It did not reach the ground, but instead exploded about five thousand metres above the forest, releasing somewhere between ten and thirty megatons of energy. That puts it firmly in the power range of a thermonuclear bomb, and means that if such an event were to one day happen over a populated area, the effects would be catastrophic.

Of course, we still don’t know precisely what hit the Earth in 1908. Some researchers argue it was an asteroid, others think it was a chunk of a comet. Papers have been written saying it was a piece of antimatter, a black hole, or even something called “mirror matter”. Some deny it came from space at all, and that it was instead some bizarre and rare burst that emerged from inside the Earth.

Most of the uncertainty comes from the lack of any clear evidence on the ground. Kulik never found an impact crater, as indeed might be expected if the impactor exploded high up. The depressions and pits he observed were probably a natural consequence of the thawing ice, rather than anything caused by rocks raining down.

But later expeditions did find small spheres of metal embedded in the soil and in the resin of trees. Detailed examination found these spheres to be rich in nickel and other metals often found in asteroids. That supports the idea of a violent explosion in the sky, one which vaporised the incoming object and scattered fragments of it across the landscape, even if it doesn’t tell us precisely what it was.

Something similar will inevitably happen again. Impacts the size of Tunguska occur once every few centuries. Smaller ones happen on the scale of decades. A Hiroshima-sized fireball, as we have seen, takes place about once every five years. The responsible objects are not big – indeed, the Tunguska object may have measured only fifty or sixty metres across.

And although we are making efforts to detect them, the work remains far from complete. Small objects still routinely slip through our net – the Chelyabinsk event was wholly unexpected, and so far only a handful of asteroids have been spotted before they hit our planet. Yet progress is being made. Surveys have already identified the largest and most dangerous asteroids out there. None, fortunately, will hit us any time soon.

Luckily, too, much of the world remains uninhabited. The next big impact is more likely to strike over an ocean than over land, over a desert than over a city, and in doing so spare us a more terrible outcome. But the odds will not always be in our favour: had the Tunguska impactor struck slightly later it might not have exploded over Siberia, but over northern Michigan. Such an event would have been far harder to ignore.

As for the mystery of exactly what exploded in Tunguska in 1908, we will probably never know for certain. The event was too long ago; the evidence has sunk into the marsh or long since faded away into myth and legend. Perhaps, in the end, we should simply leave the explanations to Agdy. Today, marking the spot under where the fireball erupted, there stands a totem to the Old Man, the God of Fire and Thunder. This remains his land.

Read More

On Progress and Revolution in Physics

Speaking generally, we might say science progresses in two distinct ways.

Was There Life on Mars?

A year ago, the Perseverance Rover discovered a rock on the surface of Mars. That happens a lot, of course, but this rock was special. For one thing, it lay amidst a region we think was once a riverbed and through which water slowly moved. The rock showed clear signs of this – it was streaked with a substance called calcium sulphate, a mineral often deposited by slow-moving river water.

The Mysterious Origins of the Third Interstellar Comet

Three weeks ago, a robotic telescope in Chile spotted a comet moving …

Tunguska was a very unlucky asteroid \ comet \ thing... very bad timing, hahaha... WW1, Russian \ Soviet revolution, then WW2... also bad placement, middle of Siberia... poor thing... only one per millennium, and getting lost like that...

The sheer scale of this event is what gets me. A 10-30 megaton airburst is almost incomprehensible. It's fascinating that the lack of a crater was the biggest puzzle for so long, and that the solution: a total vaporization of the object in the atmosphere, is almost more frightening than a ground impact. It really drives home the importance of modern detection efforts.