The Week in Space and Physics: Shades of Dark Matter

On dark matter, the sterile neutrino, Martian lightning, and the end of MAVEN.

Two short notes this week:

I have recommended Dr Larry Krumenaker’s excellent newsletter on astronomy to many of you before. He is now (re-)launching The Classroom Astronomer, a newsletter focused on astronomy education and resources for all levels. If you are interested in learning more about the practical art of astronomy, it is well worth checking out.

In the past few weeks I have been working on collecting and re-editing several of my best articles from the past two years. As a trial of an alternative to paid subscriptions, I plan to soon offer this collection in a digital magazine/booklet format. Current paid subscribers will get it for free, for everyone else it will be available at a reasonable price. More information to follow in the coming weeks!

For almost a century, we have known galaxies do not move as they should. Something else seems to be out there. Something invisible to our eyes, yet something that exerts an irresistible pull on the matter we can see, and that therefore accounts for this mysterious motion.

We call this dark matter, and calculations show that there must be a lot of it. Indeed, if we are to account for the way galaxies spin and move, we must add about ten times more matter than we can see – and that implies the visible universe is only a small fraction of the total. The problem, of course, is that we have no idea about the true nature of this dark substance.

Most researchers reckon it must be made of some unknown class of particles, ones that can exert a gravitational pull but emit little in the way of light or any other kind of radiation. Yet, under some models of dark matter, its presence might be betrayed by a faint signal of gamma-rays. Though the particles themselves do not give out this radiation, they are expected to interact through the weak nuclear force. If they do this, the particles can occasionally collide, convert into other particles, and release gamma-rays in the process.

This signal is expected to be very weak. But if it is there, it will show up around the edges of galaxies, where dark matter is thought to cluster in large halos. Efforts to find it have thus focused on surveying nearby galaxies with gamma-ray telescopes. Until now, however, little solid evidence has emerged to suggest it really exists.

In November, however, Tomonori Totani, an astronomer at the University of Tokyo, claimed to have found it. He examined fifteen years of observations of our galaxy taken by the Fermi Telescope, an orbiting gamma-ray observatory. After accounting for every possible source of gamma rays – from cosmic rays to vast bubbles of gas – he found a slight signature remained.

The signal looks similar in shape to the expected dark matter halo around the galaxy. It also matches some predictions of how this dark matter particle might act. According to Totani, this is a huge breakthrough: it is, he said, “a major development in astronomy and physics”.

Yet, there is reason to be sceptical. For one thing, there are other unexplained gamma-ray signals out there, including one shining in the heart of our galaxy. These might be coming from dark matter, but they might also be coming from some other unexpected source. Just because we see a signal, sadly, does not mean we know what is causing it.

The End of the Sterile Neutrino?

There is, of course, no shortage of other ideas about what dark matter might be. Some physicists think it could instead be made of a particle called the “sterile neutrino”, a fleeting and almost invisible particle that would interact only through gravity.

In theory, the idea is attractive. Neutrinos are already mysterious and hard to detect. They emit no light, and interact with other kinds of matter only through the weak nuclear force. In practice, that means they barely interact at all: a neutrino can pass through an entire planet without ever actually colliding with or being deflected by another particle.

The sterile neutrino, however, would escape the pull of the weak force as well. That would make it essentially impossible to detect. As neutrinos have almost no mass, even their gravitational pull would only be significant in large numbers – as if, for example, they clustered in enormous halos around the edges of galaxies. Naturally, then, we have no current proof that they exist at all.

But there are known gaps in our understanding of neutrinos. For one thing, even though standard theories suggest they should be massless, like the photon, experiments suggest they do in fact have a very small, but non-zero, mass. The sterile neutrino might, therefore, emerge from the cracks in our current theory, and thus turn out to exist after all.

Fortunately, there are experiments we can do to try spotting their subtle influence. Two of these have been running for the past few years in Germany and the United States. KATRIN, running in Germany, has made careful measurements of the electron neutrino, one of the three known varieties of the neutrino. If the sterile neutrino exists, it should create a slight change in the properties of this particle – something that KATRIN can spot.

The other, MicroBooNE at Fermilab, is looking at how muon neutrinos transform into electron neutrinos. Again, the sterile neutrino should influence the details of this transformation, and so this experiment could also hint at their presence.

Sadly, however, new results from both experiments have shown no signs of the particle. That doesn’t mean the particle can’t exist, but it does undermine many of the theoretical reasons for believing it might.

But then again, neutrinos are nothing if not surprising. More neutrino experiments and observatories are being built across the world. One of them, given enough time, may still end up revealing the closely guarded secrets of dark matter.

Lightning on Mars

When Mariner 9 approached Mars in 1971, researchers were dismayed to find the entire planet shrouded in dust. Winds blowing down a long valley had swept up clouds of dust from the slopes of Hellas, and this had spiralled into a storm of global proportions. By the time Mariner arrived, the surface of Mars – from deepest valleys to highest peaks – was obscured by a cloud of dust forty miles deep.

Such things are a constant danger on Mars. Global storms erupt once every few years, and then take months to abate. Smaller ones happen all the time, and have been observed on many occasions by probes and orbiters. But now, for the first time, researchers have found signs they produce thunder and lightning.

The discovery came from the Perseverance Rover. Microphones on board picked up clapping sounds as dust storms passed near the rover. At first, researchers thought this was explained by grains of dust hitting the microphones. But a follow-up found they were linked to small bursts of electromagnetic energy – and this could only be explained if small sparks of electricity were crackling in the Martian atmosphere.

This is probably caused by electrical charge building up as dust particles dance and collide in storms. This happens on Earth too – most visibly in the ash clouds thrown out by volcanoes – but since our atmosphere is thicker, far more charge needs to be present to cause lightning. On Mars, with its thinner air, even small dust devils can spark thunder and lightning.

Farewell to MAVEN

NASA lost contact with MAVEN, a spacecraft that has been in orbit around Mars for more than a decade. According to operators, MAVEN was functioning normally on its final contact. However, the spacecraft then passed behind Mars, and did not re-establish communication upon its return.

MAVEN’s scientific instruments have helped researchers study the atmosphere of Mars and how it interacts with the solar wind. But the probe also acted as a radio relay, transmitting signals between the rovers on the surface of the planet and operators back on Earth.

There are a handful of other relays operating around Mars, but the loss of MAVEN will cut overall communications capacity. Few new relay satellites are planned – and with the Trump administration seeking to cut the budget available for such missions, the prospects for a new one any time soon are poor. Barring a miraculous revival of MAVEN, this looks like a sad loss to our efforts to explore the red planet.

Read More

Notes On Learning Hard Things

The number one most read page on my site is a guide to learning physics.

The Biggest Solar Flare of 2025

The Quantum Cat is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

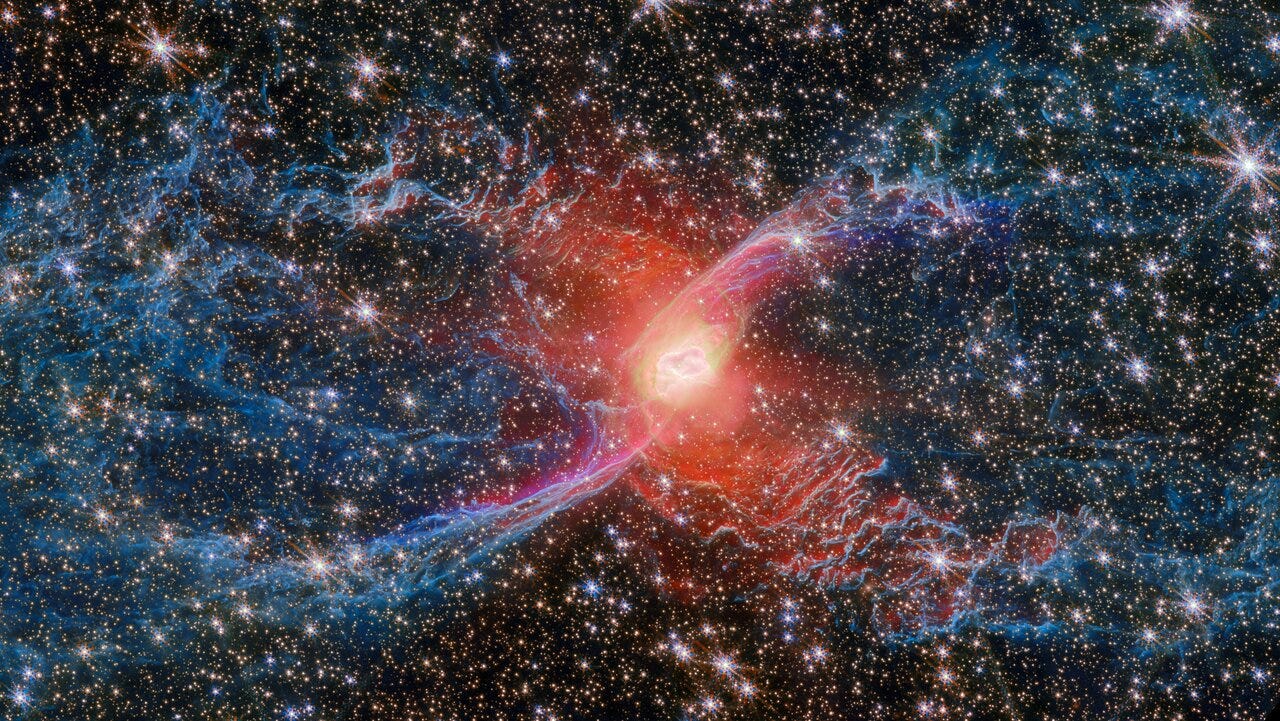

How Dust on the Ocean Floor Hints at a Recent Near-Earth Supernova

However big you imagine a supernova to be, the reality is certainly bigger. To put it one way, an exploding star can briefly outshine the combined light of every other star in a galaxy; to put it another, a supernova at the distance of Pluto would hit you with more energy than a hydrogen bomb exploding just outside your front door.