The Week in Space and Physics: Stars Beyond The Supermassive

On the most massive stars ever imagined, the launch of Artemis II, Cloud Nine, and the first private space station.

Just how massive can a star get?

The Sun makes for a logical starting point. It is big, weighing in at over three hundred thousand times the mass of the Earth. But by cosmic standards, that is merely average. Betelgeuse is about fifteen times more massive. Eta Carinae – a star so unstable it occasionally erupts in spectacular detonations – is five times more massive than even that.

But the most massive star known with reasonable certainty is RMC 136a1, a star of almost three hundred solar masses. Located in the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud, it burns with an astonishing luminosity. Were it located at the distance of Alpha Centauri, it would shine as bright as the full moon in our sky; fortunately, or sadly, it is more than a hundred thousand light-years away and visible only through telescopes.

RMC 136a1 is so big that we struggle to explain how it could possibly have formed. It is about twice the expected mass limit for stars, and so some astronomers think it might be the result of other giant stars colliding and merging. Whatever it was, the star is unlikely to be around for long. At such a mass it must be burning fuel at an incredible pace, and it will probably exhaust its reserves within the next two million years.

This seems to be about the limit of what is possible, at least for the current universe. But astronomers have long speculated that the first stars could have been far larger. Back then, the cosmos contained almost nothing but hydrogen, and the first generation of stars would have been very pure. That could have allowed them to swell to enormous sizes.

But just how big is a matter of debate. Entering the debate recently, Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb – he of the alien interstellar comet theory – suggested they could have exceeded a million solar masses. That would make them by far the largest stars ever to have existed, and in essence would be like combining an entire dwarf galaxy into a single star.

Each would have begun with a core weighing about ten times the mass of the Sun. This would have pulled in gas and grown at an extreme rate. At some point, which Loeb fixes at about a million solar masses, this accumulation of matter would have come to an end. Why is unclear - Loeb merely says they would have run out of gas to feed on – but at this point the star would cease defying reality and simply collapse into a black hole.

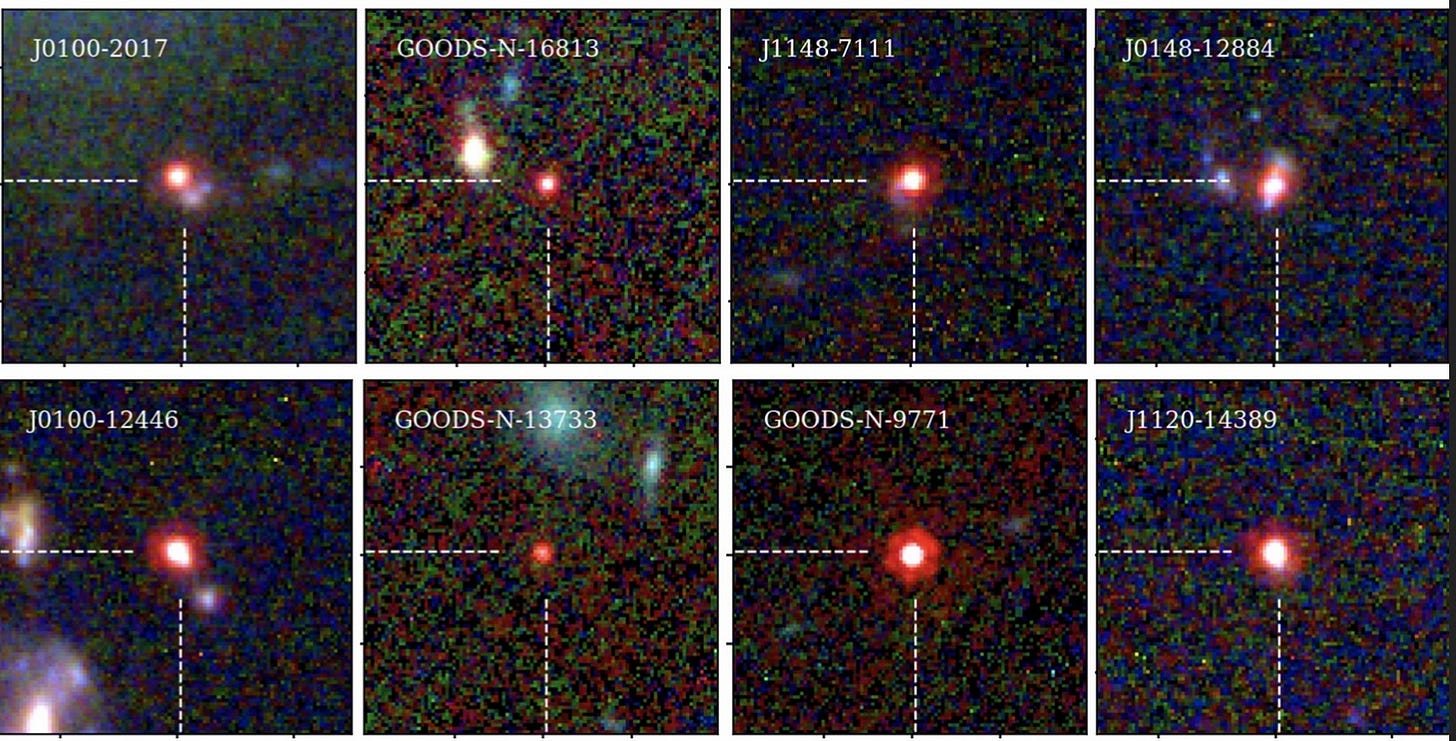

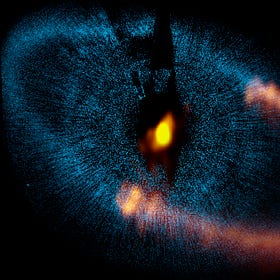

Still, there is some evidence for these stars, he says. The James Webb telescope has spotted mysterious red dots scattered across the early cosmos. All seem to be bright and fairly compact. They might, he argues, be the first generation of stars, each so massive and burning so brightly that their photons have survived a thirteen-billion-year-long trip across the universe.

But there are plenty of other explanations too. They might be giant black holes surrounded by clouds of fast-moving gas and dust. Or they could be “black hole stars”, strange objects powered by a central black hole but still shining immensely brightly. For now, astronomers are still free to speculate. So why not let some imagine they are the biggest and brightest stars ever made?

Artemis II Prepares For Launch

In the past half century, no one has ventured deeper into space than Jared Isaacman. In September 2024, he reached an altitude of fourteen hundred kilometres (almost nine hundred miles) above the surface of the Earth. That, though it does not seem like much, is as far as anyone has gone since the days of Apollo.

Perhaps it is fitting, then, that as head of NASA, Isaacman is now overseeing an effort to break that record. If things go to plan, a rocket will soon launch from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, blast a capsule towards the Moon, and send four astronauts on one of the most daring voyages of the past few decades.

The crew, which is made up of three Americans and one Canadian, will not set foot on the lunar surface. Instead they will loop around the Moon, passing about six thousand kilometres above its craters and mountains. They will then fly back towards the Earth, and re-enter our atmosphere at the astonishing speed of forty thousand kilometres per hour.

All this should prove the ability of the Artemis rocket and capsule to send astronauts to the Moon. The next step, to be done sometime in the coming years, is to prove the viability of a lunar lander. For this NASA has chosen to use Starship, a spacecraft under development by SpaceX.

NASA says Starship should demonstrate this ability before 2027, in the form of an uncrewed touchdown on the Moon. If that works, then astronauts will once again set off to the Moon on Artemis III. Once there, they will dock with Starship, transfer to its cabin, and then descend to the surface. NASA, and America’s politicians, are hoping all that can be done by 2028.

A Failed Galaxy

Modern models of cosmology say the universe should be full of dark matter halos. In many cases these surround galaxies: the dark matter came first, astronomers say, and then through the force of gravity it attracted normal matter in the form of hydrogen and helium. Later, that matter collapsed into stars, and so the first galaxies were born.

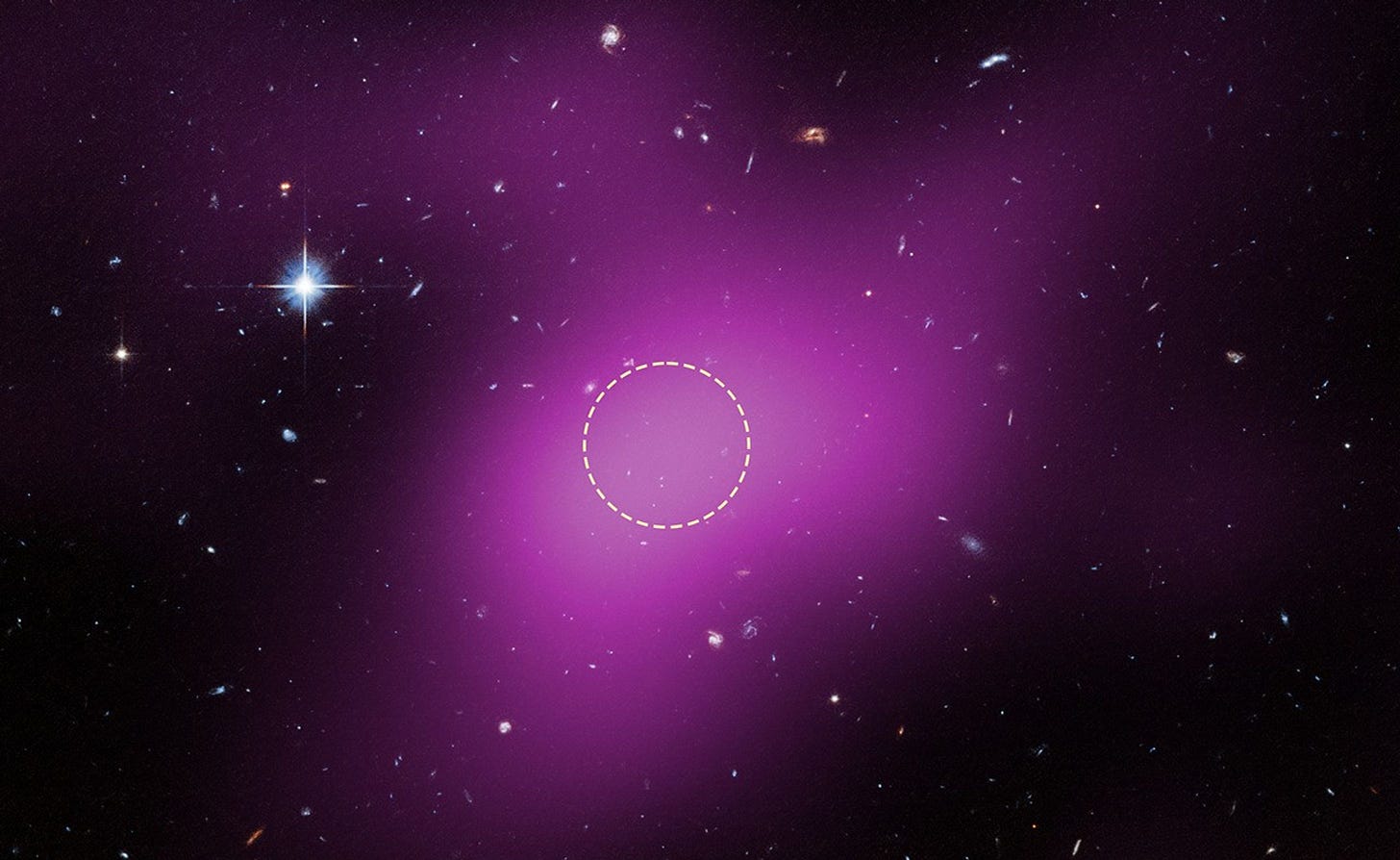

But these same models also say small halos of dark matter should be scattered around the universe. These would still attract normal matter, but not in the volumes needed to form galaxies. In theory, these halos should look like clouds of hydrogen gas, perhaps illuminated by a few scattered stars.

In practice, detecting such things is hard. But in recent years the FAST radio telescope in China has found signals coming from a few isolated clouds of hydrogen. One, located about fourteen million light-years away and named Cloud-9, looks especially interesting.

When it was first spotted, in 2023, astronomers noted it as a possible dark matter halo. But their telescopes lacked the power to spot faint stars, and so they could not rule out the possibility that this was just a small galaxy full of stars we could not see.

Now Hubble has taken a closer look. Its observations have made it clear that this is not a galaxy. There are few stars within it, and instead Cloud-9 looks rather like the long-imagined cloud of gas surrounded by a halo of dark matter.

Within it are about a million solar masses of gas – far too little to spontaneously collapse into stars. This is far outweighed by the mass of dark matter. Astronomers estimate there is about five billion solar masses of the dark stuff holding the cloud together.

The First Private Space Station

Last week Vast Space, an American startup, said it hopes to launch its prototype space station early in 2027. Though in effect a demonstration mission, the space station will be capable of hosting small crews of astronauts for two weeks at a time.

That is not much, especially when compared to the International Space Station. But as Max Haot, the CEO of Vast, said in an interview with Ars Technica, it offers an opportunity for the company to prove it can safely host astronauts in orbit.

That may help them win future contracts from NASA. As the ISS is scheduled to deorbit in the early 2030s, NASA wants commercial partners to manage future stations in orbit. If that works out, NASA would simply pay them to put their astronauts on board, much as they now pay SpaceX to launch them into space.

How well this will work in practice remains to be seen. Though several companies have talked about building private stations, actual progress has been slow. If Vast can launch next year, and if their station can host crews of astronauts, they will place themselves well ahead of the competition.

Read More

The World According to Aristotle

As nature therefore makes nothing either imperfect or in vain, it necessarily follows that she has made all these things for men

Why Not Venus?

When most people talk about sending people beyond Earth, they have one of two destinations in mind. The first is the Moon, which is lovely and all, but really a very boring place. The other is Mars, which is just about close enough for a crew to reach, rocky enough for them to land on, and with a great deal of effort might be habitable enough for them to survive on.

That million solar-mass star hypothesis is wild. Loeb's idea that they'd collapse into black holes once they hit that mass makes intuitive sense, but the whole concept feels like it pushes the boundaries of what stellar physics allows. I've been following the Little Red Dots mystery and always leaned toward the supermassive black hole explanation but treating them as remnant of primordial stars is a pretty clever alternate take.